|

"Wherever there is oppression there is resistance." "Globalise Resistance." These are the mantra of contemporary protest movements.

For much of human history oppression and resistance were localized, and the movement between them was slow. Contemporary global communication changes the dynamics -- dramatically.

The technology of communication has become smaller, cheaper, faster and more powerful. Recording devices have become small enough to carry around in your hand and cheap enough for a network to have as many as needed. Satellites with uplink and downlink have made it possible to move information from anywhere to anywhere in real time -- except for the second or two delay involved in covering thousands of miles. Increasingly powerful computers, which are also rapidly dropping in price, make encoding and editing easier and faster than ever before.

However, the economic organization of news broadcasting remains largely national, notwithstanding the potential embedded in the changes in technology. There are a few networks that aspire to a global audience instead of a national audience. CNN, during Ted Turner's ownership, was one, and WorldView was their flagship news broadcast. The program frequently began with the phrase "broadcast live around the world." BBC World is a second network that aspires to a global audience. It is not the same as BBC 1 and 2, but is a separate division that broadcasts in the U.K, and around the world. [See Global Media for elaboration of the differences between networks with a global and a national focus.]

In this report we show how networks that aspire to a global audience handle protests and demonstrations. Hence, how resistance becomes a part of an evolving global culture. We have recorded five years of news broadcasts: three years of CNN's WorldView and two years of BBC's World News. That is the database we use to characterize the practices of the two networks.

Globalizing Resistance in Day to Day Broadcasting

Time is precious in news broadcasting. WorldView and World News aired about twelve stories a day. The pool from which they chose the twelve was very large. How frequently, given this very tight constraint, do stories about protest and demonstrations make it into the news? We counted for the years 1998 and 1999 [tabular listing]. Four hundred and seventy broadcasts were recorded, and we found two hundred and sixty stories about protests and demonstrations. That is almost three stories [2.8] per week -- they show protest-demonstrations more often than every other day. Comparing this to the number of times major nations of Europe and the Far East were included in stories is one gauge of the magnitude of the number.

|

Protests

|

Germany

|

France

|

Italy

|

Russia

|

China

|

Japan

|

|

260

|

154

|

189

|

115

|

444

|

331

|

170

|

Only Russia and China were mentioned in more stories than were demonstrations and protests. Resistance is standard fare in the global news.

The reports of protests came from fifth-three countries; many countries made it into the news via the protest route. For just over half of the fifty-three countries there were only one or two stories about protests. The top ten were

|

Indonesia

|

Yugoslavia

|

U.S.

|

Palestine

|

China

|

Kosovo

|

Russia

|

Iran

|

U.K.

|

Israel

|

|

37

|

22

|

21

|

18

|

17

|

14

|

13

|

10

|

7

|

7

|

Indonesians were protesting against both the rule of Suharto and his successor as well as against the independence of East Timor. The Kosovars protested Serb treatment and Serbs protested the presidency of Milosevic once the war with NATO was over. Palestine and Israel were involved in their ongoing conflict. In China and Iran the protests were about freedoms. In Russia they were about the economy. Twenty-one protests in the U.S. were covered; the protests were about eighteen subjects. Only protests connected with the World Trade Meeting in Seattle were reported in more than one story.

The media that aspire to a global audience globalize resistance by featuring it in their news broadcasts. They fill their world with resistance against oppression -- whether it be the oppression of the Suharto government in Indonesia or the oppression of the Israeli government or the oppression of a globalizing economy. By featuring resistance they describe a world in which oppression is being resisted -- often with success.

|

|

Click Image to Play Video 0:35 seconds

|

There is a second aspect to globalizing resistance. Often, though by no means always, the protesters are making an appeal to a wider -- global -- audience. Oppression may be the winner because the deck is stacked in their favor in the local realm in which the oppression is practiced. One way to even the conflict is to appeal to a wider audience for assistance.

The Kosovars were quite successful in their appeals to a global audience in their conflict with the Serbs of Yugoslavia. Richard Blystone notes explicitly how they were making this wider appeal.

He also recounts how the success of their protests was manifest in the actions of officials attempting to mediate between the Yugoslav government and the Kosovars.

|

|

Click Image to Play Video 0:19 seconds

|

Not every group is successful, however. About the same time as the demonstrations of the Kosovars, Ocalan, the leader of the Kurdish resistance movement, was arrested and put on trial in Turkey. A million and a half Turkish Kurds live in Europe, and they began to demonstrate, in Europe, against the arrest and trial. In London they occupied the Greek embassy for two and one-half days. After making their point they left the embassy peacefully. Richard Blystone was again the reporter. There were pictures of the Kurds leaving the embassy with their hands up. There were pictures of celebrating crowds making their political message. What did they expect to gain, Blystone asked. The answer: the international media is here and for the first time people around the world are talking about the killing [of Kurds] in Turkey. They demonstrated. They hoped the communication of their concerns would win them wider support. It did not.

|

|

Click Image to Play Video 0:13

|

Some protest groups do not seem to have attempted to appeal to a wider audience. There were many protests in Indonesia during this period; more than in any other country. Nevertheless their protests were not replete with signs in a language directed at a global audience. In the 37 news stories there were one or two signs in English. The rest were similar to the ones in this snippet.

They seem to be very happy acting before a camera. They are not camera shy or threatened by the camera. Even so, the language of the signs is directed to a local audience rather than a global audience.

The distinction between addressing a global audience and addressing a local audience is found only in hints in the stories. Protesters tell who they are addressing only very rarely. They are asked who they are addressing even more rarely. Hence, we cannot count effectively. Nevertheless, it is clear that groups do differ in the audiences they address in their protests. Some groups see the global media as a domain in which they can appeal to a global audience for assistance, which is a second important factor in the media involvement in globalizing resistance.

Globalizing Resistance Against a Globalizing Economy

How the desires of the global news media to focus on important news, with protests and demonstrations fitting that criteria, and the desires of the protesters to address a wider audience work together can be nicely illustrated by following the protests against a globalizing economy and the coverage of the protests. [See Seattle, Poster Child for Protest for further elaboration]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WTO 1999: It started in Seattle. The ministerial conference of the World Trade Organization met at the end of November and the beginning of December in 1999. It was the third meeting of the body; they had met in 1996 and 1998. The leaders of the nations of the world arrived in Seattle to start a new round of trade negotiations. They were joined by protesters who wanted to stop the negotiations if possible or to influence them if stopping them was impossible. The protesters acted badly. The police acted badly, in turn. It was a spectacular confrontation between protesters and police. That was the start of global media coverage of protests against the globalizing economy.

There had been earlier protests. The Seattle police prepared a document describing the protests at the 1998 meeting and preparations for the meetings in Seattle that included appendices on: Continuum of Force; Prisoner Processing; Mutual Aid Deployment;: L-l Munitions & Chem Irritants; and Chemical Irritants Resupply. They had a good idea about what was coming. Apparently, the news media had a good idea about what was coming, as well. They had not covered the 1998 meeting; they had missed the action in Geneva. They were ready for Seattle. When the spectacle started they were there to record it.

Seattle was the first global media coverage of protests that would continue for several years. It also was the starting point for two trends in the interaction between political leaders, protesters, and media.

One trend was about coverage. The Seattle coverage told viewers almost nothing about what was happening inside the meeting or about the complaints of the protesters. It was coverage of the spectacle. The closest they came to presenting what leaders hoped to do and what protesters disagreed with was: broadcasting the first part of President Clinton's welcoming speech; and a protest leader complaining that by covering the spectacle they were ignoring the important issues that concerned the protesters. The coverage would change; the spectacle would recede and coverage of work and disagreements would increase.

The second trend was the response of political leaders to the spectacle. After becoming the object of protests and the coverage of the protest they went into hiding. The World Trade Organization is an example of this strategy. They met in Seattle in 1999. Seattle is very accessible. Their next meeting was in 2001, and it was held in Doha, Qatar. It is difficult to find a more remote location. Protesters were not given visas, and the meeting was un-protested.

DAVOS 2000: The second meeting-protests was the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, Switzerland in January 2000 -- only two months after the WTO meeting. The World Economic Forum is a private organization that epitomizes what the protesters wanted to protest -- the cozy relationship between global capital and the governments of the nations of the world. The registration fee is an indication of the wealth required to be invited to the meeting; in 2000 the registration fee was $20,000. In preparation for the meeting the government denied requests for a permit to protest, but that was overturned by the courts. On Friday only three protesters were in evidence, and the global media dutifully showed them in action. Saturday was a bit different; more than a thousand protesters descended on the tiny ski resort. The meeting was sequestered behind cordons of police. There is not much to 'trash' in a ski village so they turned to MacDonalds -- a symbol of global capital. They trashed MacDonalds -- a far cry from the destruction they visited on Seattle.

A driving snow storm helped minimize the protests in 2001 [CNN], but in 2002 the World Economic Forum escaped to New York City. New York is a city large enough for a few thousand protesters -- who did show up -- to be lost in the crowds.

International Monetary Fund and World Bank 2000: The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have a general meeting every year. The meetings are held at their offices in Washington D.C., which is quite an accessible site. Protest planners were energized by their success at Seattle [Burgess], and they wanted to push forward. The policies of the IMF and the World Bank are policies that they disagree with strongly. The protesters arrived by the thousands, but not as many thousands as in Seattle. The spectacle was less spectacular. And the media turned their attention to the work of the World Bank and IMF assisting nations with great poverty. The president of the World Bank described what they were doing. A protest leader gave her take on the working of the two institutions. Viewers learned a bit about the work and the disagreement.

May Day 2001: The next opportunity for protest -- with global media coverage -- was May Day 2001. May Day is one of very few [more or less] global holidays. As such it received considerable attention from the global media. In the period we covered they had a story the day before and another on the first of May. The stories were not about a single site; the story could skip from Cuba, to London, to Germany, and then to Russia. Implicit in this hopping from place to place is a celebration of the planet wide sharing in this holiday. In 1999 and 2000 the focus of the story had been conflict between anarchists and neo-Nazis in Germany. In 2001 the coverage turned to the anti global economy demonstrations. In 2001 and 2002 the stories remained broader than the economic protesters, but protesting the globalizing economy was the central focus.

The G 8 2001: Summer. The leaders of the G 8 nations were meeting in Genoa, Italy. The carabinarie were assembled by tens of thousands. They thought themselves prepared, but they were not. Protesters arrived by the hundreds of thousands. The world saw little other than destruction to property and the clash between protesters and police. Spectacle was back. And the politicians decided to go into hiding. In 2002 the G 8 met 40 miles outside of Calgary, Canada. Calgary is not exactly Italy, and 40 miles into the mountains was enough to keep protesters and the global media at a safe distance.

2002: The political leaders were in hiding. The WTO ministerial conference did not meet. That left the World Bank and International Monetary Fund and May Day to carry the load. But the focus of attention of the global media was already turning.

War Trumps Economic Protest

|

|

Click Image to Play Video 0:50 seconds

|

When the World Economic Forum met in January of 2003 the talk -- and the protest -- was not about the economy. It was about the war which everyone expected to come. The reporter stood in the snow recounting the events of the day. The conclusion -- the Americans are very isolated here. Global capital is alienated by the American war and what it will do to the economy.

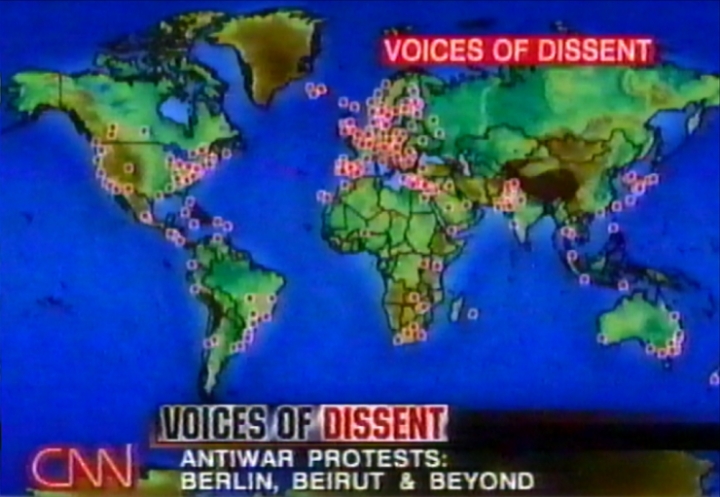

Two weeks later -- February 15 -- and the rest of the world marched to express their opinions about the war that they also expected.

It was spectacular spectacle -- 60 countries, 600 cities, millions of people. They marched to the tune of JUST SAY NO.

|

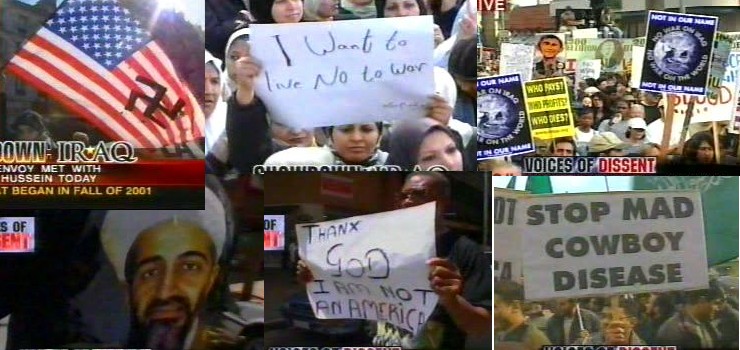

Around the world -- Berlin, Beirut & Beyond -- every people, every color, every religion joined to sing and shout their opposition. And the global media was there. CNN was piping it in from all over the world to re-distribute to the world -- that everyone would understand that they did not march alone, that they were joined by millions.

|

|

Click Image to Play Video 0:59 seconds

|

The images were powerful.

|

A swastika, not in my name, stop mad cowboy disease -- I want to live; no to war.

This global outburst seems even more remarkable when put in the context of what had gone before.

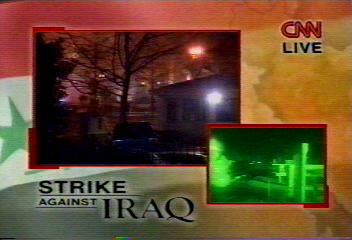

Iraq 1998: After a year of negotiations with Iraq, the U.N., and a collection of nations with an interest in Iraq, which ended in frustration, Clinton and Blair bombed Baghdad in 1998. The bombing started on December 16 -- just in time for the evening news -- and went on for several days. Then they left Iraq bounded on the north and south by no fly zones and by restrictions on the oil they could sell. There were protests in Iraq. The only protest outside of Iraq that was reported was:

|

|

Click Image to Play Video 0:45

|

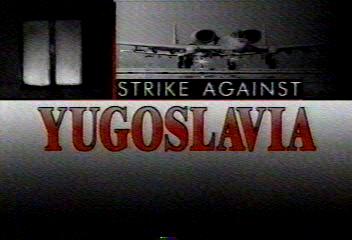

Yugoslavia 1999: After a year of negotiations NATO presented Yugoslavia with an ultimatum in the spring of 1999. Withdraw from Kosovo and stop the ethnic cleansing or we will attack you. Milosevic apparently did not believe them.

|

|

Click on Image to Play Video 0:37 seconds

|

The bombing began at the end of March and ran through June. During the three months WorldView did seventeen stories about protests against the bombing. Four of the stories were about protests in Yugoslavia, and one was from Macedonia. Another four were stories about protests in Russia. There were three stories about Chinese protesting the bombing of their embassy in Belgrade. The U.S. said it had been a mistake. The Chinese did not think that a very good excuse. There was a story about protests in Germany, and a story about Serbs protesting in the U.S. Only three stories covered a number of nations. The most extensive coverage came very early in the campaign on March 26. There had been three days of bombing, and protesters organized to oppose what NATO was doing. The protests reported were in Greece, Canada, and Russia. These protests numbered in the thousands. That was substantially more than the protests reported about the 1998 bombing of Iraq. But much short of the 2003 protest.

Afghanistan 2001: [I acquired the indexing program just in time to use beginning in September 2001. The indexing did not 'take' for much of the fall, however. I am not sure what happened, but I cannot search systematically. Going through day by day it appears that 2001 is roughly comparable to 1999. There was a series of protests in Pakistan and Iran. There were scattered protests elsewhere. At least, that is how it appear at this point. I will go back and index the broadcasts again before I can take this much farther. I am going to treat it as equivalent to 1999.]

Three wars -- 1998, 1999, and 2001. There were protesters in each. Some were people who objected to the killing in any circumstance. The Pope is the most distinguished of these, though the Pope did not join any of the protests. And there were people who had a connection to the country being warred against and who objected because of the connection. That is the picture the global news media paints of protests in the three wars. Always there, but never very many. Then the explosion in 2003.

Apparently, you have to do war exactly right to energize resistance by millions.

Conclusion

The research started with the idea that examining the coverage of protests about the globalizing economy would yield insights into how the media that aspire to a global audience deal with protests and demonstrations around the world. The Seattle protests caught the attention of politicians, citizens and scholars. There are three points about that series of protests that are noteworthy.

The first is the pattern in the dynamics of protest and coverage. With Seattle, the protests burst on the scene. But there was several years of preparation before Seattle; a series of protests that did not make it into global news, but that police and media were following. Then it was pushed off stage. War trumps protests about the economy -- even for the protesters. That pattern is not really news. It is one of the standard dynamics in broadcasting.

Second, the pattern of becoming object of protest and then hiding was not anticipated. Politicians want to be in the news. Apparently they do not want to be in the news as the objects of protest. The WTO hid. The G8 hid. In its own way the World Economic Forum hid. In hiding they took platforms away from the protesters; the media would think the protests less important because there were no politicians there to be the objects. How that would have worked out, had it not been pushed off stage, is an interesting mystery.

Third, the coverage started with the spectacle. Over the next couple of years the coverage of protests and violence receded, and viewers began to learn something about what was at stake.

At that point it seemed appropriate to place this series of protests into the context of the day to day broadcasting in this specialized media. That produced a quite remarkable number -- there are stories about protests and demonstrations every other day. They are producing a culture full of clash -- good guys against the bad guys, if you can only discern which is which.

Then 2/15; millions rose in protest against a war that was threatening. Was it protest against war -- any war? Was it protest against this war that had not been justified to their satisfaction? By comparing the protests in 2003 to the protests against warring in 1998, 1999, and 2001 one concludes that -- apparently, you have to do war just right to energize resistance by millions.