|

Leading with Blood in the Streets:

Global Broadcasters, Protesters, and Democratic

Leaders

Francis A.

Beer

G.R. Boynton

Global communication becomes easier and cheaper every year. News broadcasting increasingly aspires to a global audience that did not exist before. It produces cultural cues that both respond to the interests of the emerging global audience and that structure the understanding of global affairs of the audience.

Globalization and democracy are two additional major themes in the current practice and study of world politics. We are writing about what broadcasting, protest, and democracy become in a media that aspires to a global audience. Global news broadcasters, protesters and democratic politicians are a triple. How the relationships between them work out in the global domain is what we will report.

Globalizing News Broadcasters

CNN's WorldView and BBC's World News are the global broadcasters we have followed. We recorded the programs of WorldView from 1998 through 2000. We recorded the programs of World News from 2001 through the first half of 2003. That provided almost 1200 broadcasts for our research.

CNN's WorldView was a news program that was broadcast for a global audience. They often opened the broadcast saying "seen live around the world." Ted Turner is said to have issued an edict -- we do not use the word 'foreign.' Since 'we' are everywhere, there is no where that is foreign. BBC's World News is also a program that aspires to a global audience. Both structure their programs to appeal to a global rather than a national audience.

Serving a global audience has many consequences for their programming. They are global in their story selection. Eighty-five to ninety percent of their stories are about global affairs [Beer and Boynton, Global Media]. That is very different from nationally oriented news programs. ABC, NBC, and CBS evening news programs, for example, devote only fifteen to twenty-five percent of their stories to global news.

Further, their audience is not of one mind on any subject. That leads them to want to be on both sides of the line in war situations [Beer and Boynton, From Behind the Lines]. They wanted to be in Iraq when the U.S. and Britain were bombing in 1998. They wanted to be on both sides of the line in Yugoslavia in the conflict over Kosova. To do this they cannot 'wave the national flag.' They have to be what will be considered even handed in the most extreme situation -- else they will get tossed out or, worse, will get tossed into jail.

There are other principles of programming that they carry from pre-global broadcasting. The one relevant for this presentation is: if it bleeds it leads. From the police blotter and the local evening news through wars and other international disasters this is the practice of news broadcasters. Protests are spectacle with the ever present possibility of violence, and as such they fall within the 'if it bleeds it leads' practice.

Protest is spectacle when millions of people all over the world march to protest the policy of their government or someone else's government.

|

|

Click image to play video 0:59 seconds

|

Protest is spectable when tens of thousands are getting their heads banged together and property damage is both the reason and the result.

|

|

Click image to play video 0:32 seconds

|

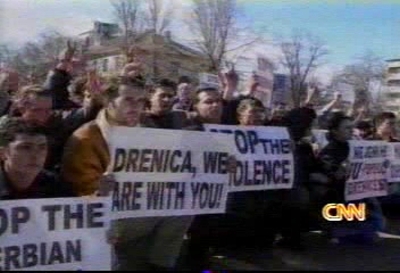

Protest is spectacle when thousands march silently in protest against the political bondage they suffer.

|

|

Click image to play video 0:14 seconds

|

Protest is dramatic. It is suspenseful. It makes good television. And the media will always be there because if it bleeds it leads.

Globalizing Protesters

Political protest is ubiquitous in the global mediascape. More than 200 stories about protests and demonstrations were broadcast each year between 1998 and 2003. The five years that we studied saw protests at World Trade Organization meetings; protests at European Union meetings; protests in Indonesia under Suharto and, later, Kosovo and Macedonia; protests against the U.S. invading Iraq; protests as U.S. presidents traveled abroad, and many more. There are 643 days on which there is a reference to protest or demonstration in the dataset.To get a handle on what this implies we produced a 'normed' 20 day month so the numbers would be comparable. The minimum number of references for any month was 0 and the maximum for any month was 20. The mean is 12 per month with a standard deviation of 3.6.

|

|

Mean Number Stories Mentioning Protest Per Month

|

On average there were three days per week on which protests or demonstrations were mentioned. The world of global communication is full of protest and demonstration. The global media serve up a steady stream of protest as spectacle.

Protest is not spectacular, however, if the protesters are few in number. It takes organization to get large crowds together. It is not full time work so you have to abandon your normal life to go off to get your head banged by the police. So, why do they do it? The news broadcasters would like to bring the answer to that question to their audiences. So they ask, and this is the answer they get. First, in England.

|

|

Click image to play video 0:11 seconds

|

Then at Genoa

|

|

Click image to play video 0:23 seconds

|

The answer is the same. We protest because they will not listen when we do not protest. Why do protesters do it? Because otherwise the political elites will not listen.

Protest is both voice and participation. It is democracy in action. It is also the practice of Schattschneider's principle: if you are losing broaden the conflict.

|

|

Click image to play video 0:47

|

Before protest, their voice was ignored by Yugoslav political elites who had already decided. Protest broadens the conflict because they can call on 'if it bleeds it leads.' The global media is their ally in raising their voice, in communicating what they want to say to a broader audience. It is their chance to broaden the conflict with the hope of changing the mix of forces at work. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it does not.

Globalizing Democratic Leaders

Protest is only necessary when political leaders have committed themselves and are unwilling to consider other points of view. Protest is, therefore, a challenge to the authority of political leaders. Democratic leaders do not like this very public challenge to their authority any more than do other political leaders. In addition, the protests, and accompanying violence, raise question about their competence as head of state. The more damage done by the protesters the more likely the question about the leader's competence. Political leaders, thus, have two reasons to want to silence protest.

The succession of protests beginning with Seattle in 1999 followed by protests in a number of venues, and then May Day 2001 and the following G8 meeting in Genoa illustrate how this triangle of persons and principles works itself out.

These are the scenes from outside the WTO meeting in Seattle in 1999 -- scenes shown round the world by CNN's WorldView.

|

|

Click image to play video 0:45 seconds

|

And these scenes from May Day in London 2001 were broadcast around the world by BBC World News.

|

|

Click image to play video 0:18 seconds

|

The G8 summit of 2002 in Canada presented quite a different picture. This is the scene of protests broadcast by BBC World News.

|

|

Click image to play video 0:28 seconds

|

There were protesters, we were told. We just did not get to see them. The leaders were protected by 55 miles and an army of check points. No one could get through.

2003 and 2004 followed suit. Leaders met, a few protesters assembled, and there were no pictures. Protest was silenced.

Conclusion

Protesters attempted to broaden conflict by taking advantage of the news media's principle -- if it bleeds it leads. As long as the protesters were willing to sacrifice their heads they made the news -- expanded the conflict.

Democratic leaders turned that rule back on the protesters. If there is no blood there is no story. All the democratic politicians had to do was to effectively disappear. Go 55 miles away from civilization or go to a state like Qatar that would not give visas to protesters or go to an island off the coast of the U.S. Isolate the leaders from all scrutiny. There is no blood. And the protest is silenced.

Globalizing media broadcasters and protesters lead with blood in the streets. Globalizing political leaders, on the other hand, can not lead with blood in the streets. Globalizing communication and political actors thus perform the interactive logic of globalization, playing out the mutually renforcing incentives of globalization. They dance together on the world stage, the big screen of world news.