GLOBALIZING SYMPATHY

Francis A. Beer

Department of Political Science

University of Colorado

G. R. Boynton

Department of Political Science

University of Iowa

Aristotle would have called it pathos.

|

|---|

| Click image to play 0:42 seconds |

"You are not alone," said American Vice President Gore as he tried to comfort the people devastated by the winter storm in Maine. It brought ice, snow, wind and freezing temperatures. Trees fell, power lines snapped, heat and light flickered and disappeared. People left their homes to survive. Livestock huddled together and died. The storm destroyed what it touched.

We saw the cattle dying; we looked at the people's faces and wanted to reach out, to help. The Vice President spoke for us when he said -- you are not alone. Pathos drove us to action, and we were able to help through FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency. It is our federal government institution that reaches out to assist fellow Americans who are in trouble. FEMA was there in this winter storm. FEMA is there for tornado victims, for flood victims, for victims of rain and snow and fire. We reach out as a national community, via FEMA, to say you are not alone. Seeing drives the pathos, and it is the seeing that connects the feeling. The sight of our fellow citizens' plight is all that is required to produce the pathos that moves us to action.

The technological changes of the past fifty years have transformed seeing. Once we had to be there to see. Now the camera takes us into the heart of the story. The movement of camera images from anywhere to anywhere in seconds has brought the 'there' to 'here.' The experience of seeing was once limited to neighborhood; then it broadened to encompass the nation. The 1998 television broadcast transmitted the images of the suffering in Maine to the entire nation -- we all saw.

As the seeing becomes national so does the sympathy and the willingness to reach out to help. News broadcasting turns seeing into pathos. The production of pathos does not stop at national borders. A few networks have developed a global broadcasting reach. What happens when the whole world is potentially 'here and now' in the seeing? What happens depends, in part, on the practices adopted by networks that aspire to a global audience. These practices are our subject. We look at two news programs, CNN's WorldView and BBC's World News. Over two and one-half years, 1998 through 2000, we recorded broadcasts of WorldView, and we recorded two and one-half years of World News during 2001 through 2003. WorldView often began by saying, "this is WorldView, broadcast live around the world." While World News does not use that phrase it is clear that they also aspire to a global audience.

We address two features of global disaster broadcasting: 1) the scope of disaster coverage and 2) the method of disaster performance, the way that disasters are turned into tragedies. This process is at the heart of "globalizing sympathy," emotional connection with a global audience.

Covering Global Natural Disasters

We examined eight hundred and twenty-five broadcasts to find reports of disasters. In addition to 'natural' disasters a few 'man made' disasters were included in the counts. Airplane crashes, train wrecks and oil spills were reported much like storms, earthquakes, and other natural disasters. However, they were only ten percent of the stories about disasters.

|

CNN WorldView & BBC

World News

|

|

|

Total Broadcasts |

Broadcasts with Disaster |

|

825 |

229 |

Every fourth day there was a story like the story about the winter storm in Maine. There were two hundred and twenty-nine stories about disasters over the 825 days. The stories ranged in length from ten seconds to eighteen minutes. About one quarter of the stories were less than one minute in length. Half the stories ran one to three minutes, and a quarter were three minutes or more. The brief stories were normally part of the around-the-world-quickly feature that both news programs used. But coverage of an earthquake in Turkey or a threatening hurricane on the eastern seaboard of the U.S. could fill most of a broadcast.

Disaster is ubiquitous. However, disaster is not one; it is highly variable. Avalanche, epidemic, drought, earthquake, volcanic eruption, famine, fire, flood, hurricane, and tornado are major natural disasters through which humans must live. The disasters with twenty or more stories during the period we counted were: epidemics, drought, earthquakes, famine, floods, and tornados. Nature regularly visits disaster upon humanity, and the news broadcasters are there to record it for us -- their audience.

|

Disaster Coverage |

||

|

Epidemics |

Drought |

Earthquakes |

|

Famine |

Floods |

Tornados |

Fifty-one countries were disaster victims. The stories were almost equally distributed through the regions of the world.

|

Areas of World |

Stories |

| Africa |

31 |

| Asia |

35 |

| Europe |

31 |

| Middle East |

16 |

| Americas |

28 |

| United States |

66 |

There were thirty-one stories from Africa: five or more stories about disasters in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Sudan, and South Africa. There were thirty-five stories about disasters in Asian nations. There were ten stories from China and four from each of India, Indonesia, Japan and the Koreas. There were thirty-one stories from Europe with France, Italy, England and Austria having four or more stories. The region with the fewest stories was the Middle East with only sixteen stories. There were ten stories about Turkey, which meant almost no stories from other Middle Eastern countries. The Americas had the largest number of stories. Excluding the United States there were twenty-eight stories with four or more stories from Brazil, Ecuador, and Colombia. The United States was the location of sixty-six stories. The United States had no earthquakes or volcanic eruptions during the six years, but it had more than its share of tornados. The United States was dominant in global news broadcasting during this six years. There was a story about the United States in more than ninety-five percent of the 825 news broadcasts. Compared to all stories the United States had relatively few stories about natural disasters.

Tragedy is a weekly experience for the global audience of these news programs. The audience regularly sees humans suffering from fires, earthquakes, droughts, and storms. One-fourth of the stories are about suffering in the United States, and three-fourths about suffering in the rest of the world. There is more than ample opportunity for globalizing sympathy.

Experiencing Global Natural Disasters

Every week the global audience sees and hears about a natural disaster and the human suffering produced by the disaster. What does the audience see and hear? How are the disasters presented? How is the argument from pathos made? There are four distinct visual presentations of the disasters: 1) up close and personal--embedding the audience as a participant in the disaster; 2) surveying the scene--assessing the scope of the disaster from a distance; 3) observing the scene--assessing the disaster at closer range; and 4) feeling the faces.

Embedding

|

|---|

| Click image to play 0:44 seconds |

We, the audience, are following a tornado. The skies are dark; the winds are high; we are moving swiftly. Suddenly the tornado veers toward us. Screams! The vehicle spins around and speeds away. We do not see the vehicle. We do not see the people who scream. We only see the tornado -- getting closer and closer. We do not know if the video is from a tornado chaser or a news photographer, but it does not matter. We are embedded in the experience. We are right there. The news reporter talks over the video while describing the path of the storm and then its devastation. That invisible voice is our only anchor in the visual storm.

Embedding viewers in the experience of disaster is more feasible for some disasters than for others. A tornado is a volatile and dangerous phenomenon, but tornado chasers do chase and record the storm. Hurricanes are easy. They may take hours to fully develop in a location. The camera can be in the wind and rain and waves. We can see the trees bending in the wind, the rain poring down and the waves crashing against the coastline. We are on the beach as the storm approaches.

|

|---|

| Click image to play 0:20 seconds |

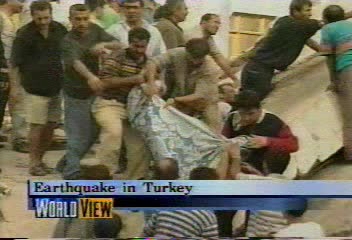

Some disasters happen so quickly that it is very unlikely that the news media will have pictures during the disaster. The pictures are taken after the disaster has occurred. An earthquake, for example, lasts only seconds. Earthquakes in Turkey and Italy were over by the time the cameras arrived. In Japan, however, a TV station had cameras already running when the earthquake hit. They had video of the skyline shaking and video of the inside of the studio shaking, tables and chair moving, and TV personnel grabbing anything that seemed to be stable.

Droughts take months to develop. The hunger that results from droughts can be visualized, but the process of drought does not do video.

Watching and listening on the shore, as the storm draws closer, is not the same as in front of a TV set. However, news broadcasters do have the ability to embed viewers in an approximation of the experience. Watching the news, we also feel fear and awe at the force of nature in the disaster.

Surveying

|

|---|

| Click image to play 0:11 seconds |

The houses below are the size of toys; the human figures are tiny. Everywhere we look there is destruction. A tornado had roared through the town destroying everything in its path -- except for one row of houses. Across the street, down the block the houses are leveled. Only one row of houses is untouched. A tiny island of survival emphasizes the devastation produced by the tornado everywhere else.

We are looking down. We see the destruction. We see that the entire town has been destroyed by the tornado. We must be in a helicopter, but there are no sounds of the helicopter. The only sound is the narrator talking over the picture we are seeing.

What we see is the scope of the destruction. Earlier, we had been embedded in the path of the tornado. Now we can see what it has wrought.

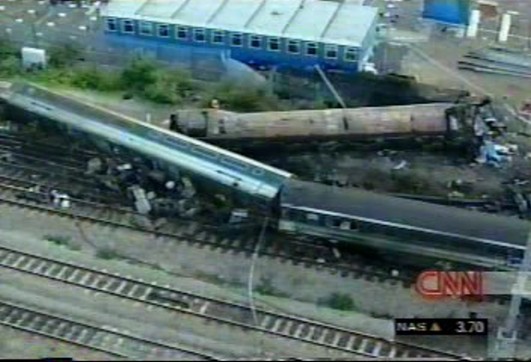

Distance is not limited to tornados. An entire train wreck can only be seen from a distance.

|

|---|

We are shown the train wreck from the air whether it is a wreck in an isolated area of Colombia or just outside of London. From a distance we can survey the extent of the damage.

The animated hurricanes used by weather services survey the scope of disaster from a distance. We see the breadth of the swirling storm; we see its center. The path of the animation lets the reporter point to where it may touch land -- here and here and here.

The scope of disaster is often wider than the human eye -- or a camera -- can see. If we are in a tornado we cannot see where it has been and where it is going. If we are standing next to a train wreck we cannot see all of the cars that have been damaged. Stepping back by one means or another -- physical distance, narrator voice-over, historical context --lets viewers see the total damage scene.

Observing

Visual distance permits us to observe the scope of the damage. However, news broadcasters supplement distance shots with views of a human scale. Much of the time the camera takes the position of an observer. It looks where a human would look. It sees just what a human would see with the same angles and the same barriers to a full view. It places us in the scene, not as a participant, but as an observer.

|

|---|

| Click image to play 0:29 seconds |

We observe attempts to rescue victims of the disaster. In Turkey and Italky buildings had crashed the ground as the earth quaked: apartment buildings in Turkey and a school in Italy. The people in the buildings were trapped. Many were killed instantly, but some survived -- trapped, waiting for rescue. We see people tearing at the rubble trying to rescue. We see teams of expert rescuers listening for sounds of persons trapped, working to dislodge obstructions, and in a few cases bringing a person out of the rubble to the cheers of other observers.

In Mozambique the disaster was water, a flood of historic proportions. Tens of thousands were stranded. Their houses were flooded, the roads were flooded, they stood in water waist deep, their only refuge was trees. There was no food, no water -- despite the water imprisoning them -- and no way out. Only helicopters and boats could save them. Wading through the flood water they made their way to the helicopter that could only carry a fraction of them.

We observe the results -- up close. We see the barren land and the dust swirling across the countryside in a Tajikistan ravaged by drought. We see the fires blazing in Borneo, and we see the orangutans that escape the fire only to be caught by the people. We see entire housing complexes destroyed by tornados in the southeastern United States.

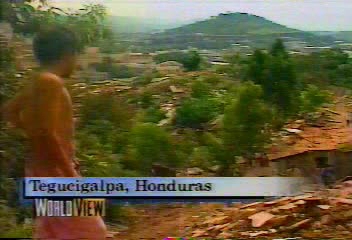

|

|---|

| Click image to play 0:36 |

We observe people trying to put their lives back together. Hurricane Mitch devastated Central America. In Honduras and Nicaragua tens of thousands died. Housing was destroyed. Water and sewerage facilities were destroyed. Roads were washed away. Crops were destroyed. After a week of destruction the storm was over. The dead had to be buried. People carried everything they could from their destroyed homes. They had to stand in line for water that was probably contaminated. The capital was cut off from the rest of the country. Bulldozers and earth moving equipment began to rebuild the road. People had to travel by foot to get food into the capitol as well as into remote villages.

There is no distance in these pictures. The camera, and we the viewers, are right in the middle of the devastation. We see the damage. We see the suffering it has brought.

Faces

How do the producers start a story about an international conference organized by the United Nations?

|

|---|

| Click image to play 0:03 |

With the faces of small children -- children from around the world. The conference was scientists meeting to report on their research on aids. The children, and others like them, are at risk from aids. Showing their pictures is a way of saying, this is what the conference is about. It is about a healthy life for children. The pictures of the children are also more gripping for viewers than are pictures of scientists talking.

We recognize the suffering in the faces of victims. To show us the suffering the camera zooms in, closing in tight on the faces. The faces dominate the entire screen; they are all that we can see.

We see the faces of famine in a story about Ethiopia. A terrible famine in 2000 causes tens of thousands of people to starve to death. The rains did not come in 2002. Another famine was on the way. The video of the story begins and ends with faces: the faces of famine. The faces of emaciated children announce the horror to come. The story ends with a small child being fed -- only his head and the cup from which he is eating are visible. And the worried face of a mother.

The eyes are often the most expressive element of the faces.

|

|---|

During the middle of the winter, high in the mountains of Afghanistan, an earthquake struck. The houses of entire villages were destroyed. People were thrown into the cold. Without help they could not survive. They traveled with whatever they could carry on donkeys to points where helicopters or trucks could reach them with aid -- tents, blankets, food and water. And they waited -- faces waiting for assistance. And in the center of the picture are the Afghan eyes -- dark, haunted eyes. Those same eyes would be more widely seen only a few years later when the U.S. and allies invaded Afghanistan. The same dark, haunted eyes would appear on international magazine covers.

|

|---|

| Click image to play 0:37 |

The numbers of AIDS victims in South Africa are staggering. The inaction of the government is difficult to understand. But the faces of suffering are the most difficult to watch. The reporter is taken on a tour of a shanty town filled with men and women and children afflicted with AIDS. He walks into the room of a woman with tiny twin girls. They all have AIDS. "I wanted to kill myself," she says. "What will you do?" he asks. Then something quite unusual for television -- silence. Her hand goes to her face in silent despair and the camera zooms in until that image of pain and torment fill the screen.

We see the suffering in their faces. We see it in their eyes. The pain and despair is universally recognizable. The news broadcasters tell us stories of disaster and despair, and they show us the disaster and despair in the faces.

Conclusion

Global news disaster broadcasting transports us into the heart of darkness. It turns seeing into tragedy, producing the pathos of fear and awe on a worldwide scale. It provides a gaze from near and far, where the audience both participates and observes. It embeds viewers in the situation, steps back to gaze at the scope of the damage, and then draws us back in. It observes the people responding, it shows us the faces of disaster and despair.

Are global media mainly theater, or do they provide more than virtual presence and vicarious entertainment? Do they make a difference? Do they persuade? Do they lead to relief? Some aid workers believe that they do. They were in Sudan. By 1998 Sudan had already suffered years of famine and more was to come. But assistance had been slow in coming. UNICEF received less than half the funding it requested. Why? "There was little media attention to the starving in Sudan so donors did not care," they said. International organizations are ready to step in with assistance in disasters around the world just as FEMA stands ready to help in the United States. But the international organizations need support; they must draw on financial support from the nations of the world.