The Rhetoric of Global Leadership

Cooperating, Crusading, and Preparing for War

Francis A. Beer and G. R. Boynton

Global communication provides a new domain for political leadership and public rhetoric at the beginning of the 21st century. The reach of CNN's WorldView and BBC's World News is global, and it is a global audience to which they aspire. The emergence of global news broadcasting has opened a new theater, with new settings, for political agents and political action. While all political leaders would like to appear on the stage, only a few get speaking parts. Media managers must see a political leader as "important," and the leader's speech and action as "news," in order to provide space and time. The editors and reporters fit bits and pieces of political leaders' talk into their news stories as they create together the rhetoric of global political leadership (see Beer and Boynton, 2004a,b,c; 2003, 2001, 1999; Hariman, 1995; Hauser, 2004; Nelson and Boynton, 1997).

Our research focuses on news broadcasting that aspires to a global audience. We recorded two and one half years of CNN's WorldView between 1998 and its demise in 2000 and BBC's World News from 2001 through the first half of 2003. These news broadcasts are far more global in their choice of stories than are news broadcasts that aspire only to a national audience. We examine their coverage of four events: Iraq 1998, Yugoslavia/Kosovo 1999, the Twin Towers and Afghanistan in 2001, and Iraq 2003. Political leaders and news broadcasters alike understood these as important episodes of prudent political rhetoric.

Media Stories of Political Leaders Preparing for War

The rhetoric of leaders preparing for war is the specific subject of the analysis. How much coverage is there? Which political leaders get to speak? How much do they talk? In later sections we turn to: What do they say? How do they say it?

The conflict between Iraq and the United Nations in 1998 and Yugoslavia and NATO in 1998-99 were intertwined, with the focus of attention shifting from one conflict to the other. In 1998 there were 288 stories about the conflict between the United Nations and Iraq. There were 264 stories about NATO and Yugoslavia between March 1998 and March 1999.

|

Table 1

News Stories of Iraq and Yugoslavia Conflicts: 1998-1999 |

||||||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | June | July | Aug | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan | Feb | March | Total | |

| Iraq | 28 | 71 | 26 | 17 | 6 | 20 | 3 | 16 | 11 | 12 | 38 | 40 | 288 | |||

| Yugoslavia | 31 | 8 | 10 | 26 | 16 | 11 | 16 | 42 | 0 | 14 | 17 | 33 | 40 | 264 | ||

Table 1 shows the conflict between the United Nations and Iraq peaking in February, 1998 with 71 stories. It was only defused when Secretary General Kofi Annan worked out an arrangement for inspections that was acceptable, for the time being, to both sides. Attention to Iraq then subsided until the end of the year. In November, Iraq threatened suspension of inspections, then agreed to inspections again, and finally stopped inspections in December. At the end of December the United States and England bombed.

Yugoslavia was in the news in March, 1998, when it appeared in 31 stories as it undertook military action against the Kosovars. Attention then receded until the 42 stories of October, when U.S. Ambassador Richard Holbrook worked out an agreement with Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic that was acceptable, for the time being, to both sides. Attention to Yugoslavia/Kosovo dropped in November and December, but the arrangement broke down as the Yugoslav military again attacked the Kosovars. Coverage picked up in February, and NATO began bombing in March.

The story of theTwin Towers/Afghanistan obviously began as a surprise; it did not have a preliminary buildup. There were more than 100 stories about the Twin Towers and Afghanistan during the three and one half month period between September 11, 2001 and the end of the year.

Iraq was a major focus in the news for the entire year preceding the the second U.S. Invasion in the spring of 2003. There were approximately 20 stories per month with very little variation between months.

United States leaders dominated CNN WorldView's and BBC World News' coverage of preparing for war. One way to note this is by counting the number of times political leaders and international organizations appear in the stories about the conflicts.

|

Table 2

Political Leaders Preparing for War |

|||||

|

Iraq 1998

|

Kosovo

|

Afghanistan

|

Iraq 2003

|

Total

|

|

| Number of stories |

288

|

264

|

107

|

229

|

882

|

| Clinton/Bush |

106

|

79

|

33

|

88

|

306

|

| Blair |

15

|

1

|

4

|

15

|

35

|

| Albright/Powell |

37

|

31

|

3

|

9

|

80

|

| Cohen/Rumsfeld |

19

|

10

|

3

|

12

|

44

|

| Annan |

48

|

7

|

|

2

|

57

|

| Butler/Blix |

52

|

|

|

20

|

72

|

| United Nations |

131

|

46

|

12

|

68

|

257

|

| NATO |

|

110

|

1

|

16

|

127

|

| Solana |

|

5

|

|

|

5

|

| Chirac |

2

|

0

|

|

25

|

27

|

| Kohl/Schroeder |

0

|

3

|

|

6

|

9

|

Table 2 shows that there were 882 stories about the conflicts leading to war. U.S. presidents Clinton and Bush were mentioned in 306, or 35%, of the stories. No other political leader came close to the attention focused on the U.S. presidents. The United Nations was mentioned second most frequently in about 30% of the stories. Equally telling is the frequency with which the U.S. secretaries of state and the U.S. secretaries of defense are mentioned relative to people in those positions in other countries. The ministers of foreign affairs or defense of other nations are almost never mentioned in the reporting.

What is not evident from these counts is the depiction of the United States as the principal moving force in the controversies. The United Nations was heavily involved in the controversies with Iraq, but it was the United States, with assistance from Britain, that spurred the U.N. to action according to the news reporters. The conflict with Yugoslavia was a conflict organized by NATO. However, U.S. Secretary of State Albright was always seen pushing for action to curtail Yugoslav behavior in Kosovo. The attack on Afghanistan was not a United Nations or NATO operation; it was a "coalition of nations" or an "international coalition" led by the United States -- phrases used in 31 of the stories about the conflict.

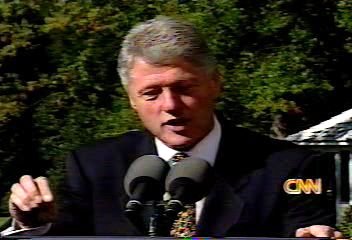

The United States dominated the news, but presidents were not quoted frequently. Heads of state were often mentioned as part of the story, but they spoke only rarely. For example, President Clinton was mentioned in 106 of the 288 stories about the conflict between the U.N. and Iraq. Most of these were references to the Clinton administration or to actions he was said to be taking. He spoke, as Table 3 shows, in only 15 of the stories in which he was mentioned. Prime Minister Blair was the only head of state other than U.S. presidents who was referred to in many of the stories, but he was pictured talking only 8 times across the four episodes. Heads of state talked infrequently in the news and, such talk was largely limited to the presidents of the United States.

|

Table 3

Presidents Clinton and Bush Speaking |

||||

|

Iraq 1998

|

kosovo

|

Afghanistan

|

Iraq 2003

|

|

| Clinton |

15

|

10

|

|

|

| Bush |

|

|

18

|

26

|

Reporters and editors of WorldView incorporated Clinton talking into 15 of their stories about Iraq and 10 stories about Kosovo. Reporters and editors of World News incorporated Bush talking in 18 of their stories about Afghanistan and 26 of the stories about Iraq.

They did not speak often. They also did not speak long. The news broadcasters used only brief clips of the presidents talking in their stories.

|

Table 4.

Average Presidential Speaking Time in Seconds |

||||

|

Iraq 1998

|

Kosovo

|

Afghanistan

|

Iraq 2003

|

|

| Clinton |

21

|

19

|

|

|

| Bush |

|

|

35

|

22

|

They talked 21, 19, 35, and 22 seconds on average. Brief snippets were selected from much longer speeches and interviews. One of president Clinton's speeches was not counted in computing the Iraq 1998 average. He talked to the nation the evening the bombing started. He talked for fourteen minutes and the entire speech was broadcast by an extended WorldView. Only one other speech in the collection was as long as two minutes; the opening statement of Bush for an interview when president Musharraf of Pakistan visited the U.S. in November of 2001. In a rather perverse way one can think of these brief clips as relatively full. U.S. news broadcasts that focus on a national audience have politicians' speaking time down to nine seconds (Adatto, 1993).

Two Rhetorical Tasks

The rhetorical styles of Presidents Bush and Clinton were quite different; differences that may be accounted for by the different rhetorical tasks they set for themselves. The tasks structured both the words and the tone of their speaking.

Clinton worked to build and hold together a cooperative coalition of nations opposing Iraq's refusal to permit United Nations inspectors to do their work. It also opposed the Yugoslav police/military treatment of the Kosovars. Clinton's task was to persuade nations to act together.

Bush set his task as leading a crusade against terrorism and evil (see Stoessinger, 1979). Persuading other nations to act together does not seem to have been as important as directing the United States into a war on terrorism. The task was to persuade U.S. citizens that a war on terrorism was necessary, noble, and likely to be successful.

Let Us Act Together

Two themes dominated Clinton's speaking: the actions to be opposed, and the need to act together. The actions to be opposed were Iraq's development of weapons of mass and the Yugosalvia's crimes against the Kosovars.

|

|

Weapons of Mass Destruction

|

In his first statement on January 28, 1998 Clinton began with "we know . . . weapons of mass destruction." "We know that Saddam has used weapons of mass destruction before," he said. It was one of his most consistent themes. The video to the right presents three of his statements about weapons of mass destruction. He hammered home the danger. "Weapons of mass destruction" was an explicit theme in eight of his fifteen statements about Iraq, and it was the unspoken but assumed basis for criticism in the other seven. The threat was qualified by the action that Clinton was willing to envision taking -- bombing. Bombing could not destroy all of Saddam's production facilities, he said, but "it can and will leave him significantly worse off than he is now." Either Saddam will destroy the weapons of mass destruction and the facilities for creating them, and let the United Nations inspectors verify the destruction, or we will act to destroy the facilities.

|

|

Not Regime Change

|

In an early statement, on February 5, Clinton made it clear that weapons of mass destruction were his focus. Would Iraqis be better off if there was a change in regime? Yes, he said, but that is not what we have been authorized to do by the United Nations. It is not what we can count on other nations to approve. In this one brief statement, Clinton joined his two major themes and added a minor one. One, weapons of mass destruction must be dealt with; regime change is not on the table. Two, the nations of the world have authorized the United States to act for them if action is necessary. The minor theme: his expressed desire for a diplomatic solution rather than military action joins these two themes. "What I hope most of all," he said, is for Saddam to move away from his present position to a diplomatic resolution of the conflict.

|

|

Nurturing the Coalition

|

Clinton was not so much announcing a coalition of nations as he was nurturing one. "We intend to be very firm on this and I hope we will have the world community with us," he said in the clip above. On February 10 he announced that Canada and Australia had agreed to join the U.S. and allies if military action was required. The language was the language of bringing nations together.

I am very pleased by the support from all around the world.

Friends and allies share our conviction.

Canada and Australia are prepared to join us, England, and our allies if Saddam will not do the will of the international community

If military action becomes necessary I am grateful that so many nations are prepared to stand with America

He used the language of sharing, sharing a concern and a willingness to act, and the language of being grateful for the sharing. We were standing together.

Nurturing the coalition was manifest in two other statements. Russia was the ally least inclined to approve of using force against Iraq. When asked about Russia's opposition on February 13, Clinton recalled the working relationship he had had with Russian President Yeltsin and how they had worked together to advance the cause of world peace. But you could not simply walk away from the U.N resolutions if diplomacy fails, he said. Nyet could not be no in this context.

|

|

|

Nyet Cannot be No

|

Consulting with U.N.

|

In March, Clinton reinforced his commitment to work within the framework of the United Nations. Kofi Annan had just negotiated an arrangement with Iraq, and Clinton congratulated him. But if Saddam did not comply, Clinton said, the current resolutions would permit us to move -- after further consultation. Annan replied that consultation was the way the international community worked together. Clinton acted to keep the coalition in place even after the resolutions were on the books.

|

|

Bombing Iraq

|

Back and forth it went -- disagreement, followed by agreement, followed by disagreement. Finally, the nations of the world had had enough. In December, Britain and the United States bombed facilities they believed were involved in producing weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. They bombed with the unanimous support of the U.N. Security Council of the United Nations. Russia had been convinced; China had been convinced. The nations of the world were acting together -- though some more reluctantly than others.

It was apparently a difficult decision for Clinton. His face, his eyes were those of a man who had struggled with the enormity of his decision. Innocent Iraqis would die as a result of his order.

The story of Kosovo was very similar. What had been weapons of mass destruction in Iraq became violence in the Balkans. And the United Nations became NATO.

|

|

|

Violence in Balkans

|

NATO

|

The media images had already done the work. CNN had been covering the uprising in Kosovo for months. They had shown pictures of thousands of people marching in protest. They had shown pictures of people massacred. They had shown pictures of families fleeing their homes to get away from the Serb military. Clinton did not have to press the case for action; the media had already made it. Clinton also seemed quite confident about this coalition. Russia and China had to be convinced to agree to the U.N. resolution. But the NATO alliance would do the work, and he seemed assured that they were ready.

His words were measured. The settings and the tone were formal. The audience he was addressing was first Saddam and Milosevic. Give it up, he said. The audience was secondarily the coalition he was nurturing. They are committing acts we cannot tolerate. If they do not give it up we must act. The American people were third. Americans must know about the acts of aggression. Americans must know that a coalition of nations is acting together. In the end Americans must know that these actions are in their national interest.

Leading a Crusade

|

|

September 11, 2001

|

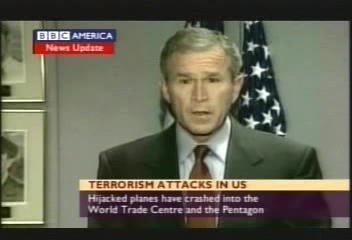

"Freedom itself was attacked this morning." Not 'we.' Not 'America.' Not 'life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.' In his first public words after the explosions of 9/11 -- speaking from the bunker in Nebraska -- Bush set a pattern that would continue throughout his war on terrorism. He was speaking to Americans; he was not speaking to the rest of the world.

The attack on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon shocked the globe. The world press covered the event almost to the exclusion of all other news. They carefully reported Bush's first speech and his speeches in the days after September 11. The one theme they did not pick up from his speeches was 'freedom' (Frensley and Michaud, 2004). Only in America, and particularly in the right wing of American culture, is freedom so central to the self image that one can substitute "freedom itself" was attacked for 'we' or 'America.' George Bush's talk incorporated a distinctively American rhetorical tradition.

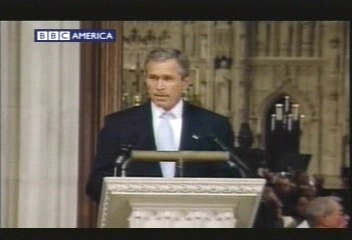

A few days later, September 14, in Washington Cathedral Bush announced that "our responsibility to history is clear -- to rid the world of evil." The world is neatly divided between good and evil, and he would, as he said later, lead the 'crusade' to rid the world of terrorism (Office of Press Secretary, 2001).

|

|

|

Washington Cathedral

|

New York Site

|

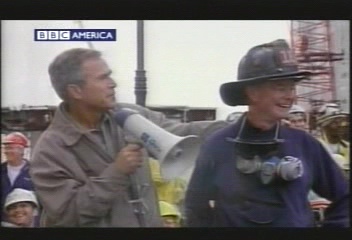

When he traveled to the site that had been the twin towers on September 14 the response of Americans to his call for a crusade on evil was a pep rally chant "USA, USA, USA."

Justice was given a distinctively American twist. There was a poster out west -- wanted dead or alive (September 17). The west and the justice of the west is an important strand in American culture. But it is distinctive to American culture. It could not resonate beyond the borders of the nation as it did within them.

|

|

|

Justice of the West

|

Progress

|

Justice became progress. It was a rather venomous recounting of the progress, but it echoed another important theme in American culture that does not have the same resonance in other nations of the world. We make progress by bringing the evildoers to justice.

The themes were strongly American, and there was little acknowledgment of the assistance that other nations were providing. When Bush was asked what the Taliban would have to do, his answer did not mention the United Nations. He did not mention NATO. Instead he said, they must turn over terrorists and destroy terrorist camps. "That's what I told them and that's what I mean," he said. It was the imperious "I" of one who felt himself fully in charge.

|

|

|

That's What I Told Them

|

Japanese Assistance

|

The United States did have help from other nations. But there were not many visits from foreign heads of state; and, when they visited Washington, Bush seemed to be going through the motions of thanking them for their assistance. On September 25 the prime minister of Japan was in Washington volunteering the assistance of his nation. As they walked out to face the reporters, Bush seemed distracted -- as though he had to stop and remember who was standing beside him.

|

|

Afghanistan Only the Beginning

|

It was Osama bin Laden who was wanted dead or alive; but, as the war progressed, the enemy expanded. First it became all terrorists. And finally terrorists became anyone harboring or aiding terrorists. Only two months into the war, Bush said, "Afghanistan is only the beginning." And Iraq was squarely in his sights. Saddam had to demonstrate to the world that he had no weapons of mass destruction, Bush said.

Bush and Clinton were now joined. Clinton had attacked Iraq because of weapons of mass destruction. Bush recreated terrorism to include weapons of mass destruction. We now know that the Bush administration considered invading Iraq immediately after September 11 but concluded that no one would believe the way to get Osama bin Laden was to invade Iraq (CBSNews.com, 2004). First the groundwork had to be laid by expanding the conception of terrorism potentially to include any contemporary nation state of significance. Then Iraq could become the next target in the crusade to rid the world of -- now newly redefined -- terrorists.

With Kabul safely in the hands of Hamid Karzai, Bush could turn his attention to Iraq. The initial arguments were familiar: weapons of mass destruction and connection with Al Qaeda.

|

|

Making the Case

|

Almost a year before the invasion of Iraq, May 23, 2002, Bush was making the case for action. In this statement he joined the threat of weapons of mass destruction with the threat of Al Qaeda.

From May of 2002 through March of 2003, Bush was shown speaking 26 times by BBC World News. The themes of the first six months were: 1) weapons of mass destruction, 2) Saddam had committed himself to disarm and he must disarm, and 3) the threat of terrorists. The first two are closely related; either he has weapons of mass destruction, or he agreed to rid himself of weapons of mass destruction. One or the other of the themes was present in seven of the first ten speeches. Terrorists only made it into two speeches during the period.

|

|

So Called Inspectors

|

Beginning in November of 2002 there was a shift in Bush's rhetoric. The threat of weapons of mass destruction morphed into we will disarm him. In the last 16 speeches Bush talked about the danger of weapons of mass destruction four times and said we will disarm Iraq four times. The language of he agreed to disarm morphed into he is delaying and hiding the weapons. By January of 2003 the weapons inspectors were in Iraq. Bush's comments on January 22 showed doubts about both the process and effectiveness of the inspectors. By stance, by tone, and by word it seemed that the only acceptable answer from the weapons inspectors would have been we have found weapons.

Bush did not have to build a coalition of nations after 9/11. The world was horrified by what it had seen; political leaders stood in line to volunteer. Bush could speak as a "pied piper" in the United States without concern for how that might be interpreted abroad. "Abroad" was already on board. That, however, was not the situation when he turned to Iraq. Tony Blair, who had worked with Clinton, was willing to go forward on Iraq with him. After that it was an uphill battle. It was particularly problematic because Bush clearly wanted to do in Iraq what had been done in Afghanistan -- regime change. There were very few nations in the world who wanted to remake the United Nations into an agency of regime change. Recruiting a coalition would take much persuasion, and what he was saying 'at home' was likely to be watched closely around the world.

|

|

Stiffing the World

|

Seventeen times between September 4, 2002 and March 7, 2003 BBC World News carried Bush speaking either explicitly or implicitly about cooperation with other nations [click to see the transcript].

It started in quite a formal setting. He invited the leaders of congress to come to the White House. They and the leaders of his administration were sitting around a large table in the White House. Television was there to broadcast the event to the world. What was broadcast seems likely to have been taken as an insult, however. "I am going to call upon the world to recognize that Saddam is stiffing the world," Bush said. Since the world knew exactly what Saddam was doing it seems, at best, presumptuous for the president to say that he could inform them that they were being stiffed. It is hard to imagine world leaders being persuaded by being told that they were being stiffed.

In September and October of 2002 Bush attempted to present arguments that could appeal to other world leaders. "I will remind them that history has called us into action. That we love freedom. That we will be deliberate, patient and strong in the values we adhere to." "History" was his war on terrorism. However, "deliberate, patient and strong in the values we adhere to" seems a deliberate attempt to sound 'diplomatic.' Even during this period he could not restrain himself from saying that either they could join or they would be left behind. "And I again call for the United Nations to pass a strong resolution holding this man to account. And if they are unable to do so the United States and our friends will act." There were five statements broadcast in September and October. In three he seemed to be trying to accommodate the sensibilities of world leaders. In the other two he could not restrain himself from saying that he would act without regard for what they thought if they disagreed with him.

|

|

Mirth in the White House

|

November arrived, and the balance in the tone of his public statements changed noticeably. Laughing, relaxed, informal -- the president and his men met in the White House to communicate with the world. November 12 was four days after Hans Blix had agreed to lead United Nations weapons inspectors to determine if Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. "It's over. No more delays . . ." In saying that, Bush denied the premise of the commission to Blix. There was no question about Iraq having weapons of mass destruction. "He must disarm." Bush already knew the answer. He did not have to wait for weapons inspectors to report. Bush also "stiffed"' the nations of the world. He set the timetable. It was over. No more time was required, even though the Security Council had just passed a resolution setting up a procedure that would take months to carry out. He could laugh at them as he asserted his own view of the world. This seems perfectly good rhetoric for people who were already convinced of Bush's position. But it does not seem designed to convince those who did not agree. It was rhetoric that pushed doubters away.

|

|

Irrelevant Debating Society

|

February arrived and with it another change in tone. He was in full commander in chief attire. He was talking to sailors gathered for the occasion. It seemed that Iraq might comply with the requirements of the Security Council resolution that established the weapons inspectors. So, "the decision for the United Nations is this." Will you become an "ineffective, irrelevant debating society?" The words and the demeanor were a sneer.

A few days earlier he had spelled out his invitation more fully. "No doubt he will play a last minute game of deception. The game is over. All the world can rise to this moment. The community of free nations can show that it is strong and confident and determined to keep the peace. The United Nations can renew its purpose and be a source of stability and security in the world. The Security Council can affirm that it is able and prepared to meet future challenges and other dangers." The game was over for Saddam. Free nations could show that they were strong and confident. The United Nations could renew its purpose. The Security Council could affirm that it was able. How? By following his lead. If not they would fade into history as an ineffective, irrelevant debating society. This was the rhetoric of a poor loser. He had not won the support of the members of the Security Council. He had not won the support of the nations of the world. So he did what an adolescent might -- he picked up his marbles and dropped them on the people of Iraq.

|

|

Permission

|

We don't need anyone's permission, Bush said on March 3. Then on March 20 he ordered the invasion of Iraq. On May 2 he landed on the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, declaring "mission accomplished." He had not, however, managed to persuade many doubters to join the crusade. Italy and Spain were the major allies joining the U.S. and England. He had not been been able to persuade many other national leaders. Nor was he more successful with ordinary people. In May and June BBC conducted surveys in eleven countries around the world, and they reported the results in their broadcast of June 17. Sixty percent of their sample had an unfavorable impression of Bush and only thirty-one percent a favorable impression. Fifty-nine percent thought the invasion of Iraq was wrong. When people were asked which was the greatest danger to world peace, the U.S. was second only to Al Qaeda--North Korea, Iran, Syria, France, Russia and China were all viewed as less of a threat to world peace than the U.S.

On September 11, 2001 George Bush articulated a vision: a worldwide crusade to root out and destroy terrorism, with him in the lead. It worked in the beginning. But when he turned to Iraq he seemed to forget that he was trying to lead an all volunteer army. Conscription of followers was not an option except for a few nations whose arms he managed to twist. Recruitment required persuasion; he had to speak to the world. And his words did not persuade.

The Evolution of Global Political Rhetoric

Global telecommunications technology and practice offer the permissive conditions for global political leadership and political rhetoric. Global media provide a new platform, an expanded public domain for talk and action. The medium, as Marshall McLuhan famously said, is the message; but media do not fully determine their own use.

The players on the global stage follow their own scripts. Media elites have their own concerns, choosing stories that they feel appropriate for their tasks. Issues like Iraq ebb and flow as a focus of news attention. Political actors seize the stage to a greater or lesser degree. Though their speaking parts may be small, they can set the plot lines. The leaders are the main characters and dominate the action as reporters frame the talk.

The rhetoric of global political leadership includes different stories, characters, and performances. In the cases we examined, Presidents Clinton and Bush set different tasks for themselves and adopted different rhetorical styles to accomplish the tasks. And they addressed different audiences within the global domain. Both addressed the Other-- Hussein, Milosevic, the Taliban, and Hussein. Clinton focused on nurturing cooperative international allies, persuading coalition members to undertake collective action as team players. Bush was unwilling or unable to address a global audience in this way. His crusading performance, combining the Lone Ranger and a frontier preacher talking hell fire and brimstone, appealed mainly to parts of the U.S. audience.

In the emerging global public domain, media elites, political players, and audiences use different scripts in different situations to adapt, learn, and evolve together. Some are more successful than others.

References

Adatto, Kiku (1993). Picture Perfect: The Art and Artifice of Public Image-Making (New York, Basic Books), p. 2

Beer, F. A and G. R. Boynton. (2004a). “Globalizing Political Action: Building bin Laden and Getting Ready for 9/11” The American Communication Journal. http://www.acjournal.org/holdings/vol7/index.htm

Beer, F. A and G. R. Boynton. (2004b). “Paths through the Minefields of Foreign Policy Space: Practical Reasoning in U.S. Senate Discourse about Cambodia,” in Metaphorical World Politics, pp. 141-161 (Francis A. Beer and Christ'l De Landtsheer, eds.) (East Lansing MI: Michigan State University Press).

Beer, F. A and G. R. Boynton. (2004c). "The Globalization of Sympathy and Action" in Proceedings of the Speech Communication Association/American Forensic Association, Alta Utah 2003 (forthcoming).

Beer, F. A and G. R. Boynton. (2003). Globalizing Terror” POROI Journal 2, 1 http://inpress.lib.uiowa.edu/poroi/papers/beer030725_outline.html

Beer, F. A and G. R. Boynton. (2001). "Talking about Dying: Rhetorical Phases of the Somalia Intervention," pp. 117-138 in Francis A. Beer, Meanings of War and Peace (College Station TX: Texas A&M University Press).

Beer, F. A. and G. R. Boynton. (1999). "The World View of WorldView" in Proceedings of the Speech Communication Association/American Forensic Association, Alta, Utah.

CBSNEWS.com (2004). "Clarke's Take on Terror," March 21.

Frensley, Nathalie and Michaud, Nelson (2004). "Canadian Media Semi-Globalization and Resistance to US Hegemony," paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association, Montreal.

Hariman, R. (1995). Political Style. (Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press).

Hauser, G. A. (2004), "Rhetorical Democracy and Civic Engagement," pp. 1-14 in G. A. Hauser and A. Grim, eds., Rhetorical Democracy (Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates).

Nelson, J. S. and G. R. Boynton (1997). Video Rhetorics. Urbana IL: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Office of Press Secretary (2001). Transcript of September 16 press conference.

Stoessinger, John G. (1979). Crusaders and Pragmatists: Movers of Modern American Foreign Policy. (New York: Norton).