GLOBAL MEDIA DIPLOMACY AND IRANIAN NUCLEAR WEAPONS

The New Space of Global Media Diplomacy

Francis Beer

G. R. Boynton

When real time global communication became possible, a new media space for diplomacy came into existence. CNN led the way, and the “CNN effect” on foreign policy was born. CNN has retreated somewhat from this early mission, but other news broadcasters have stepped in to broadcast international news on both television and the internet. The websites of Aljazeera, in English, BBC World and CNN World aspire to bring world politics to a global audience, and politicians have been quick to take advantage of this new domain for action.

In this paper we begin to explore how diplomacy has become public in response to the news spaces opened by the global media. We recorded CNN's WorldView from 1998 through 2000, BBC's World News 2001 through 2003, and the websites of Aljazeera, BBC World and CNN World for 2005. We will do three things in this paper. We will illustrate public diplomacy as it has been practiced in television news broadcasting aimed at a global audience. We will provide information on the extent to which diplomacy is an important part of the news for these TV news broadcaster. And we will trace one steam of diplomatic negotiations in the websites of Aljazeera, BBC World, and CNN World.

These analyses allow us to map the actions and reactions of political actors as they are projected through the editorial filters of specific media channels. The communications are part of multilevel games and have multiple audiences. Diplomacy behind closed doors is not replaced by the interactions in the global media. But pluralistic global media communication adds a new dimension to diplomatic activity, making it more accessible, dynamic, and complex. It is this new dimension of interaction that we analyze.

Diplomacy in Public and Public Diplomacy

First, we need to differentiate what we are attempting to do from two other research programs in the study of international relations: public diplomacy and events data research. We are interested in diplomacy in public, and there is an important research tradition studying public diplomacy. It is significant, however, that we phrase our subject as 'diplomacy in public.' Public diplomacy has meant Voice of America, and other communication specifically designed for audiences of citizens. Generally the communication involved in public diplomacy is tailored for a specific national audience. The medium we are interested in is global media, the audience is the global audience these media constitute, the organizers of this communication are news broadcasters rather than government agencies. There is some overlap between what we are doing and the research into public diplomacy. When Karen Hughes was appointed undersecretary of state for public diplomacy and public affairs that made it into the global media we are examining. [Aljazeera September 10, 2005] However, we are not specifically examining her activity and the activity of her office.

Media Events and Events Data

There is more overlap between events data research and our research than between our research and 'public diplomacy.' The similarities are in the sources we use, but the focus of the research is rather different. Events data researchers wanted as complete a compendium of events as they could achieve (e.g. KEDS). They turned to the news media to locate the events. While they started with the global media of the day -- The New York Times -- they found that they needed to go to local media to fill in the events that did not make it into all the news that's fit to print. We are interested in the media that aspire to a global audience, and as a result are bringing into being a new global culture. Hence, we focus on events in the media rather than attempt to get as much detail as we could if we went to other sources. In addition, in the coding in the events data tradition there was no consistent distinction between diplomacy in public and diplomacy behind closed doors. They would capture both, but their analyses would not focus on this dimension of the data.

Instances of Globalizing Diplomacy

CNN celebrated twenty years of broadcasting in 2000 with the CNN minute. It was a year long series of brief stories drawn from their first twenty years of operation. One of the stories was about Moammar Gadhafi. [play gadhafi-call.rm, 1:30] It has a self deprecating character with a humorous twist at the end. However, the import of the story is that CNN is the domain in which global diplomacy is being practiced. If you want to enter into the diplomacy CNN is where you have to be. That, at least, is what Gadhafi was saying and what CNN was happy to remember as part of who they were. The technology of communication evolved quite rapidly in the CNN twenty years producing the potential for real time global communication. CNN took full advantage of the new technological possibilities to become a place where global news was made.

But CNN was not alone. BBC was also developing television with a global focus. When NATO began attacking the Taliban BBC was there to bring the story to their viewers. The Taliban, however, was deeply suspicious of all outsiders and particularly suspicious of the global news media. [talibannocameras.mpg, 0:46] But they had no answer to the NATO bombing. Desperate times call for desperate measures. So on November 21, 2001 they held a news conference to plead their case in front of the cameras addressing a global audience. [play talibanpressconference.mpg, 2:00] When their backs were to the wall they reached out to make their case in the global domain of BBC and CNN and other international news broadcasters. The depth of their desperation was reflected in their permiting female reporters to participate.

When you step in front of the cameras you have no control over who is watching. The audience may include people you did not intend. Early in 1998 the foreign policy leaders of the Clinton administration went to Ohio to promote public support for their policy in Iraq. Sadaam Hussein had again tossed out the U.N. inspectors, and they wanted to threaten him. The audience did not cooperate. [townmeeting98021801.mpg, 1:53] It was not the audience reaction they had anticipated. But the audience was not only the people in the room. The audience was not only the people of the United States. CNN is a global domain, and the audience was viewers around the world -- including political leaders in many other countries. The next day the reaction was in. [worldreaction98021801.mpg, 1:33] Fortunately, for the Clinton administration Secretary General Annan worked out an arrangement with Sadaam that took the U.S. off the hook. Even though it lasted only a few months it gave the Clinton foreign policy leaders time to recover from their public embarrassment.

As they had inadvertently addressed an audience of diplomats, Clinton is quite explicitly addressing the world's political leaders about Yugoslavia and Kosova in November of 1998. [clinton981002.rm, 0:12] We are acting together, he said. And Slobodan Milosevic, you need to get that message.

We are interested in what happens to diplomacy when it goes public, when the domain of action is the global communication media, when the audience reaches beyond diplomats to an interested public. These vignettes illustrate some of the characteristic features found when making the shift from diplomacy behind closed doors to diplomacy in public.

References to Diplomatic Activity in the Global Media

Diplomatic activity was one of the primary topics of reporting for CNN's WorldView. The language of diplomacy was ubiguitous.

|

Number of Days |

Language Used |

|

253 |

diplomatic or diplomacy |

|

166 |

diplomat or diplomats |

|

173 |

foreign minister or foreign secretary |

|

210 |

Albright |

|

53 |

Russian foreign minister |

|

15 |

Robin Cook, U.K. |

The words "diplomatic" or "diplomacy" appeared in 253 of the broadcasts we recorded from 1998 through 2000. "Diplomat" or "diplomats" were referred to in 166 of the broadcasts. And "foreign minister" or "foreign secretary" were used in 173 broadcasts. Madeleine Albright, then U.S. secretary of state, was referred to in 210 of the broadcasts. She was much more frequently referred to than other members of the diplomatic core. The several Russian foreign ministers during that period were mentioned 53 times, and Robin Cook, foreign secretary of England, was mentioned 15 times.

|

Reporting Madeleine Albright

|

||

|

First Story

|

Second-Fourth

|

Stories Five+

|

|

75

|

79

|

76

|

The importance WorldView gave to these stories is reflected in the placement of stories in which Madeleine Albright was mentioned. One-third of the stories were the first of the broadcast, which are the stories the network considers the most important. For broadcasts with approximately 14 stories per day appearing in the first story is a clear marker of the importance of stories of diplomacy. Another third of the stories in which she was mentioned were the second through the fourth stories. And only a third of the time was she mentioned in stories five through the end of the broadcast. [references in stories add to more than 210 because of multiple stories on some broadcasts] Diplomatic activity was top news for WorldView.

Preparing for war is the quintessential diplomatic activity. The major military activities from 1998 through 2003 were U.S. and Britain bombing Iraq in 1998, the NATO conflict with Yugoslavia over the treatment of ethnic Albanians in Kosova, the conflict with the Taliban in Afghanistan and the U.S. and Britain invading Iraq in 2003.

|

Political Leaders Preparing for War |

|||||

|

Iraq 1998

|

Kosova

|

Afghanistan

|

Iraq 2003

|

Total

|

|

| Number of stories |

288

|

264

|

107

|

229

|

882

|

| Clinton/Bush |

106

|

79

|

33

|

88

|

306

|

| Blair |

15

|

1

|

4

|

15

|

35

|

| Albright/Powell |

37

|

31

|

3

|

9

|

80

|

| Cohen/Rumsfeld |

19

|

10

|

3

|

12

|

44

|

| Annan |

48

|

7

|

|

2

|

57

|

| Butler/Blix |

52

|

|

|

20

|

72

|

| United Nations |

131

|

46

|

12

|

68

|

257

|

| NATO |

|

110

|

1

|

16

|

127

|

| Solana |

|

5

|

|

|

5

|

| Chirac |

2

|

0

|

|

25

|

27

|

| Kohl/Schroeder |

0

|

3

|

|

6

|

9

|

There were 882 reports about these conflicts -- reports drawn from CNN's WorldView for Iraq 1998 and Kosova, and from BBC's World News for Afghanistan and Iraq 2003.

U.S. presidents Clinton and Bush were mentioned in 306, or 35%, of the stories. The 'leaders of the free world' got far and away the most press. Once past the U.S. presidents the patterns reflect the diplomacy of the different events. Madeleine Albright was more active in public than was Colin Powell. Kofi Annan played an important diplomatic role in the first year long controversy with Iraq, but was not publicly connected to the other three conflicts. Butler and Blix were important actors in the controversies with Iraq. The U.N. was also particularly important in the Iraq controversies. But it was NATO in the conflict with Yugoslavia. There are fewer stories about Afghanistan than the other controversies because there was little diplomacy before the attack. The nations of the world knew who they wanted, and there was no need for diplomacy. Chirac was the most vocal critic of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003.

A Diplomatic Stream: Iranian Nuclear Production Facilities

Diplomatic activity is big news. That is the conclusion one can draw from these numbers. They do not reflect the practice of diplomacy, however. All of time is collapsed into a single sum. Most of these controversies were streams of negotiation occurring in time. Also, the numbers do not differentiate diplomacy in public from diplomacy behind closed doors. We have to examine the news reports differently to bring time and public and private into view.

November 14, 2004 Iran agreed to negotiate with England, France and Germany about their nuclear production program. The next day Iranian diplomatic officials announced their agreement to the world.

An Iranian foreign ministry spokesman told reporters Monday the decision to suspend the uranium enrichment program was a voluntary move to dispel concerns it was secretly building atomic weapons.

Hamid Reza Asefi said the freeze would only last for a short time while Iran and the EU discuss a lasting solution to its nuclear case. [CNN World, November 15, 2004]

"The suspension is valid for the duration of the negotiations," he said. "This is the beginning of the normalisation of Iran's dossier at the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency)."

Moussavian said the suspension would remain in force while Iran and the European Union negotiated a long-term cooperation accord. He said these negotiations would start on 15 December. [Aljazeera 15, 2004]

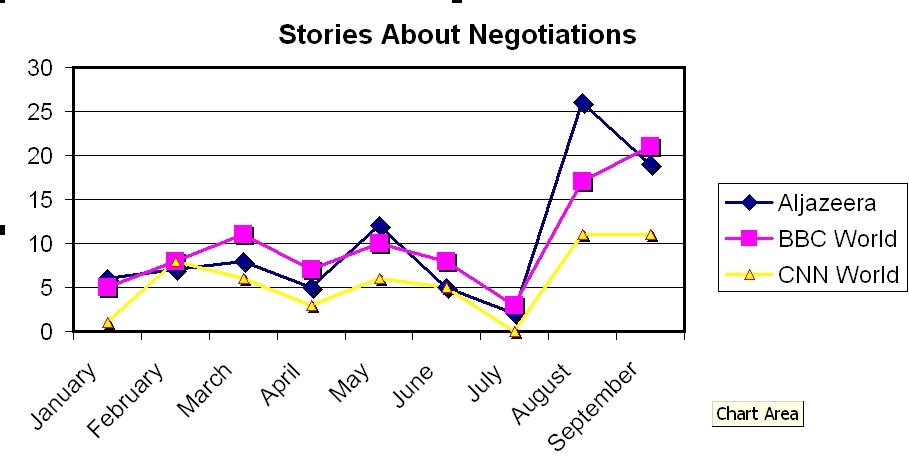

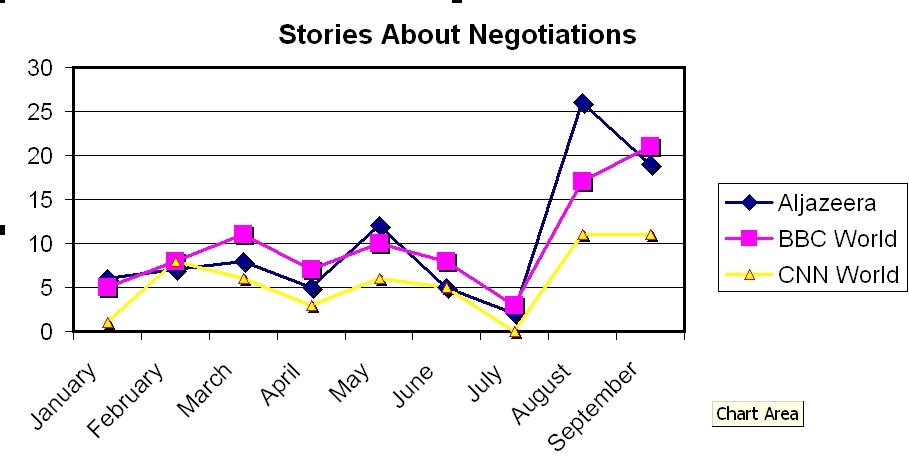

While the negotiations resulting in this agreement had run for months we will pick up the diplomatic stream at that point, and trace the negotiations, both public and private, from January through October of 2005 as it was reported on the news websites of Aljazeera [English], BBC World, and CNN World. We identified 91 reports from the Aljazeera website during the 10 months. We got 93 from BBC World and 53 from CNN World. Aljazeera and BBC World published almost exactly the same number of news reports and CNN World published roughly sixty percent as many as the other two.

|

The pattern of publication in time is also quite similar. The number of reports peaked in March and May, then fell to a very few reports in July, but August and September showed a burst of stories well above the earlier totals. We will need to come back to the timing of the diplomacy, but for now this reflects the similarity of the coverage of the three news media.

Diplomacy is largely communication whether in public or private. Talk in public is what we have in mind as diplomacy in public. While on the way to a meeting of NATO in February president Bush was interviewed.

In an interview with Belgian television, Bush said on Friday that an attack on Iran can never be ruled out.

"First of all, you never want a president to say never, but military action is certainly not, is never the president's first choice," Bush told VRT television, when asked if he could rule out military action against Iran.

"Diplomacy is always the president's, or at least always my first choice and we've got a common goal, and that is that Iran should not have a nuclear weapon," he said in the interview taped in Washington earlier and broadcast before his arrival in Brussels on Sunday for summit talks with Nato and the European Union. [Aljazeera, February 18, 2005]

He was asked the question that most concerned Europeans: Would he rule out an attack on Iran? That question must have been the reason for the interview. He could take the question and reassure the people he was going to visit that diplomacy was his route for this venture. He could also warn Iran that military action was never ruled out if it became necessary. Whether intended or not there were a number of interested audiences reading his answers and considering what the answers meant for them.

The tone was different in August.

US President George W Bush says he still has not ruled out the option of using force against Iran, after it resumed work on its nuclear programme. . . .

The BBC's Jonathan Beale in Washington says the president wants to send a clear warning to Tehran . . . [BBC World, August 13, 2005]

This, the reporter was told, is a clear message to Iran -- if you continue with your nuclear energy program we may well use force.

Diplomacy behind closed doors need not remain a secret. In this report England, France, and Germany are said to have negotiated a deal with the United States.

The three European countries negotiating with Iran -- Britain, Germany and France -- had been pressing the Bush administration to drop American opposition to Iran trying to enter the WTO, which facilitates trade between nations.

Those nations, in return, agreed to send the dispute with Iran to the U.N. Security Council if the Iranians fail to fulfill their international agreements, including a promise to halt uranium enrichment.

"I am pleased that we are speaking with one voice with our European friends," U.S. President Bush told a crowd in Shreveport, Louisiana. [CNN World, March 11, 2005]

The US would not oppose Iran entering the WTO and the European countries agreed that they would push to take Iran to the U.N. Security Council if Iran returned to uranium enrichment. No one announced the deal. It was referred to by the reporter who had gotten it from a source who was not identified, apparently, as the reporter was traveling with president Bush in Louisiana. President Bush is the only one engaged in public diplomacy when he says he is glad to be speaking with one voice with Europe. It is hard to imagine that the arrangement between the U.S. and the three Europeans nations was uppermost in the minds of the people of Louisiana. Other audiences seem more important for his statement. The Europeans were conspicuously absent.

We went through the 250 stories looking for instances of diplomacy in public and diplomacy behind closed doors. The table below summarizes what we found. Its principal utility is showing that there were only modest differences between the three news websites. If there was no difference each row would have equal numbers of entries for Aljazeera and BBC World and CNN World would be sixty percent of the entries for the other two. That is, approximately, what is found in most rows.

| Actions | Total | Aljazeera | BBC World | CNN World |

| actAnonymous | 50 | 27 | 11 | 12 |

| actEngland | 29 | 11 | 13 | 5 |

| actFrance | 27 | 13 | 9 | 5 |

| actGermany | 18 | 9 | 7 | 2 |

| actIAEAagency | 48 | 18 | 20 | 10 |

| actIAEAboard | 13 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| actIran | 144 | 56 | 58 | 30 |

| actRussia | 16 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| actUS | 73 | 25 | 29 | 19 |

| refChina | 16 | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| refEngland | 69 | 27 | 32 | 10 |

| refEU3 | 96 | 37 | 36 | 23 |

| refFrance | 68 | 28 | 29 | 11 |

| refGermany | 68 | 25 | 32 | 11 |

| refIAEAagency | 26 | 7 | 13 | 6 |

| refIAEAboard | 15 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| refIran | 46 | 18 | 18 | 10 |

| refRussia | 24 | 10 | 8 | 6 |

| refUS | 81 | 30 | 34 | 17 |

Since the three news websites are very similar in the fluctuation in reporting through time and in the distribution of instances of public and private diplomacy they can be added together to constitute a single global domain of diplomatic activity.

We want to address two questions about this stream of diplomacy in this paper. One, how did the various actors engage in diplomacy in public and behind closed doors? Two, how did this change through time?

These are the totals derived from the 250 news reports. Iran was portrayed as engaged in diplomacy in public in 144 news reports, for which we used the shorthand 'actIran.' They were much less likely to be portrayed as engaged in diplomacy behind close doors. The count for this, 'refIran', was only 46.

|

Public and Private Diplomacy

|

||||||||||

| Month | actIran | refIran | actUS | refUS | actEU3 | refEU3 | actEng | actFr | actGer | actAnon |

| Total | 144 | 46 | 73 | 81 | 6 | 164 | 29 | 27 | 18 | 50 |

The United States was not 'officially' engaged in the negotiations. The negotiations were between Iran and England, France, and Germany. That did not stop U.S. policy makers from voicing their views of the situation both in public and private. They were portrayed as speaking out in 73 news reports, and engaged in behind the scenes activity in 81 reports.

The counts for England, France and Germany need some explanation. The three nations were referred to as either EU3 or England, France and Germany when their behind the scenes activity was referred to. There were 164 reports that used one or the other of these designations. However, they were reported as collectively engaged in public activity only 6 times. Someone spoke for England, usually Jack Straw, 29 times. The foreign minister of France spoke out 27 times, and a German representative spoke out 18 times. The Germans were probably busy with their election at the time they might have engaged in diplomacy in public. Even if you add together the actions of EU3, England, France and Germany the total is only 80.

The final category of actor is 'anonymous source.' These are interpretations of the situation by officials who do not want to 'take credit' for their interpretation. Fifty news reports used anonymous sources to elaborate the situation being reported.

The pattern is: Iran reported as engaged in diplomacy in public three times as often as they were reported engaging in diplomacy behind the scenes. The U.S. is reported to be engaged in public and private diplomacy almost an equal number of times. The European diplomats were reported working behind the scenes twice as often as they were reported to be engaged in diplomacy in public.

Iran's penchant for going public seems to be straightforwardly related to the task they set for themselves from the beginning of the negotiations.

An Iranian foreign ministry spokesman told reporters Monday the decision to suspend the uranium enrichment program was a voluntary move to dispel concerns it was secretly building atomic weapons. [CNN World, November 15, 2004]

They had developed nuclear production facilities secretly for 18 years before they were discovered and turned to working with the International Atomic Energy Agency to monitor their program. They needed to convince the world that their program was for energy and not for war, and that as signatories of the Nuclear Proliferation Treaty it was legal for them to engage in uranium enrichment. The audience for these claims went well beyond the closed doors in which they were negotiating with the three European nations.

U.S. policy makers were quite open about their suspicions that Iran intended to develop nuclear weapons. They said it over and over both in public and behind closed doors. That seems to have been their chief role in the negotiations -- casting doubt on the motives of Iran.

The actions of the Europeans can be understood by looking at the pattern over time. For this purpose the nine months have been collapsed into periods -- 1) January through July and 2) August and September.

The earlier figure showed much more activity in August and September than in the months earlier. The totals for the two time periods are close even though the first period is 7 months and the second is 2 months. 346 actions were reported January through July and 292 were reported in August and September.

|

Public and Private Diplomacy for January through

July and August-September

|

||||||||||

| Month | actIran | refIran | actUS | refUS | actEU3 | refEU3 | actEng | actFr | actGer | actAnon |

| J-J | 81 | 28 | 40 | 50 | 3 | 95 | 15 | 4 | 8 | 22 |

| A-S | 62 | 19 | 33 | 31 | 3 | 69 | 14 | 23 | 10 | 28 |

| Total | 144 | 46 | 73 | 81 | 6 | 164 | 29 | 27 | 18 | 50 |

The European nations came out of the closet in August and September. Public actions were reported by them 30 times in the first seven months and 50 times in August and September. Unlike the Europeans there were more reports about Iran and the U.S. in first seven months than in the last two.

As long as the U.S. was publicly articulating the suspicions England, France, and Germany could negotiate behind closed doors. This had the advantage that if not in public they would not have to answer the second half of the Iran claim -- that under the Nuclear Proliferation Treaty they could legitimately enrich uranium. That claim was never challenged in all of the reports. It was never mentioned by the U.S. and the Europeans.

After seven months of negotiation the Iranians said enough time had passed and they demanded that the Europeans produce a concrete proposal by the first of August. England, France, and Germany produced a proposal, and Iran said no. The 'final' proposal involved Iran permanently giving up uranium enrichment. Iran said that was unacceptable, and they resumed some production that they had closed down earlier. The closed door was closed, and all the actors went public in a burst of speeches and press releases.

Two additional patterns need to be investigated to trace the diplomacy in public and behind closed doors. We need to examine the pattern of joining actors in the same report by the reporters. How often is there explicit interaction: claim and counter claim? How often are actors used to complete the reporters' conception of a story even though they have done nothing? How often is only one actor referred to in a report? The second pattern to be traced is positions the actors take in the ongoing stream. Where do they start? If they change when do they change? Both are needed, but they are beyond the scope of this paper.

Conclusion

We have focused here on new dimensions of globalizing media as they help reflect and construct the diplomacy of the 21st century. Our work suggests that emerging technology drives major media and political actors onto the world stage, where they compete with other for the attention of a global audience. Diplomacy behind closed doors doesn't go away, it also goes public when the actors deem it in their best interest.

What does diplomacy in public look like? Our preliminary investigation of global media diplomacy and Iranian nuclear weapons suggest produce at least one counter-intuitive result. There do not seem to be great differences between media actors with organizational centers in different parts of the world, in some dimensions of the case at least.. Al Jazeera, BBC, and CNN all showed simlar patterns of coverage, both in the aggregate and through time. The political actors, however, behaved differently in different time periods, some being more public, others more private at different times.

We have come a long way since the first world war at the beginning of the 20th century when Woodrow Wilson stumped for "open covenants openly arrived at" and the second world war at mid-century when " Hans Morgenthau warned against the diplomatic "vice of publicity." Diplomacy at the start of the 21st century occurs as part of a highly complex global system, both openly and behind closed doors, publicly and and privately. Political actors use the media, and media actors use the politicians to advance their interests in different ways. The question today is not whether or not there shall be diplomatic publicity, but rather who does it where, when, why, and how. The case of Iranian nuclear weapons shows globalizing media and political elites using new technologies as part of a dynamic and sophisticated diplomatic process.

REFERENCES

Beer, Francis A. and G. Robert Boynton. 2004. “Globalizing Political Action: Building bin Laden and Getting Ready for 9/11” , The American Communication Journal 7 (2004). http://www.acjournal.org/holdings/vol7/index.htm

Beer, Francis A. and G. Robert Boynton. 2003. “Globalizing Terror”, POROI Journal 2, 1 http://inpress.lib.uiowa.edu/poroi/papers/beer030725_outline.html

McEvoy-Levy, Siobhàn . 2001. American Exceptionalism and US Foreign Policy: Public Diplomacy at the End of the Cold War. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave, 2001.