PICTURE FRAMING:

IMAGES OF WAR, PROTEST, AND FLAGS ON THE

ALJAZEERA IN ARABIC WEBSITE

FRANCIS A. BEER

POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPT. UNIVERSITY

OF COLORADO

BOULDER COLORADO 8O302

Email:

beer@colorado.edu

G. R. BOYNTON

UNIVERSITY OF IOWA

POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPT.

UNIVERSITY OF IOWA

IOWA CITY, IOWA 52242

Email:

bob-boynton@uiowa.edu

Abstract

War and protest are major components of the daily news. "If it

bleeds, it leads" is a central axiom of news broadcasting. This paper examines

the way that one globalizing news network uses images to frame stories about

war and protest. Individualistic images of soldiers and weapons; death,

destruction and suffering present important visual themes. At the same

time, flag images invoke more

communal identities. We examine such images from war and

protest news stories in Arabic editions of Aljazeera websites during

2005-2006.

PICTURE FRAMING:

IMAGES OF WAR, PROTEST, AND

FLAGS ON THE ALJAZEERA IN ARABIC WEBSITE

Images as

Frames

Picture frames suggest

wooden slats surrounding colorful paintings. By the frames, we know art.

In recent

years, framing has also become a popular topic in the fields of political

communication and psychology. Political framing, in this

metaphorical sense,

focuses on

the way that context influences the meaning of public events.

Much existing research has examined the framing effects of verbal

political rhetoric (Lakoff, 2006

http://www.rockridgeinstitute.org/projects/strategic/simple_framing ;

Entman, 2003; Norris, 2003).

Recent work has separately

explored the dynamics of still and moving images in political life

(Hariman and Lucaites 2007; Nelson and Boynton,

1997). In

spite of the maxim that a picture is worth a thousand words, however,

the way that images frame public issues has not been deeply

explored. This paper moves into this space and focuses on visual

rhetorical effects. It examines the way images were used to frame war and

protest on the Aljazeera [Arabic] website between November 2005 and the end of

2006.

Images and Global Communication

The analysis of the 2005-2006 Aljazeera [Arabic] website springs

from a larger project of our own. We have been studying global

communication for a number of years (Beer and Boynton, 2007,

2004http://www.acjournal.org/holdings/vol7/index.htm

Beer, Francis A. and G. R. Boynton. 2003

http://inpress.lib.uiowa.edu/poroi/papers/beer030725_outline.html

, 2003). We started with television news programs aimed at a global audience

broadcast by BBC and CNN.

Visualization has been a central element in television broadcasting,

and an important feature of our analyses. More recently we have turned to

websites that aspire to a global audience: websites of Aljazeera, BBC and CNN.

The technology for communication on the web has continued to change

rapidly, and the news organizations followed the technology. We, in

turn, followed the news organizations, moving our research to web based

communication. This allowed us to add another 'voice' for our research.

Aljazeera has both an English language website and an Arabic language website.

We have followed both even though we cannot read Arabic. We

can, however, follow the photo images at Aljazeera [Arabic].

While visualization had been an important element in television it

appeared to be de-emphasized on the web. The websites of Aljazeera [English],

BBC World, and CNN World had photo images with almost all stories, but they

were still images rather than video and they were very small. This was

probably due to bandwidth considerations. Both the news organizations and

their readers had connections to the internet that moved information/bytes

rather slowly. We are convinced that visual communication is an important

amplification of words, and believe it is important to study the images used

by the news organizations.

Globalizing news organizations are always in search of audience. War and

violence are important in people's lives and lead them to search for news. We,

therefore, think it useful to look at images of war and protest,

which are central components of the daily news. As images appear in global

news stories about war and protest, they frame the messages the stories

convey, and they provide part of the texture that gives meaning to war

and protest. The images include pictures of soldiers and weapons; death,

destruction, and suffering; and flags. The study of these images on the

Aljazeera [Arabic] website seems particularly appropriate since the Bush

administration has felt that Aljazeera was working against

them by showing graphic images of the US invasion.

Soldiers and Weapons

Images frame war and protest in different ways. One set of images frames

war in terms of soldiers and weapons. We have such images from the

2005-2006 Aljazeera [Arabic] website.

This is the War

Zone

And this

And this

Suffering and Size

War is not only about the actions of soldiers and weapons. It is also about

destruction, death, and suffering wrought on their targets. Media

also use images to portray these meanings of war. In this visual framing,

the size of the image matters

[Bob Boynton,

http://globalizing.wordpress.com/2006/12/07/size-matters

].

Images at 'postage stamp' size are not 'worth a thousand words.' The three

English language websites have used photos at three sizes: tiny, in between,

and small. The tiny photos were used to identify the story and averaged 75

pixels by 58 pixels. The in between size average was 204 by 157 pixels; this

is the size of the photos at the top of each story. Aljazeera [English] and

CNN World each used a single photo to focus the reader on the major story of

the day, which averages 278 by 218 pixels. How these differences are important

to the communication can be shown by taking a single photo and showing it at

all of these sizes.

Tiny

|

Standard Story

|

Large Focus Attention

|

Aljazeera [Arabic]

|

|

|

|

|

The communication of the tiny size is close to zero. The standard story size

is still too small for the information that the picture could carry. The large

photo used on the front page to call attention to the lead story of the day

begins to reach a size in which someone looking at the photo can pick up on

the details of the image. Aljazeera [Arabic] has consistently put the largest

photo images on their website. Their photos measure 390 by 310. At this size

the emotional impact of the image becomes as prominent as the ability to

recognize what is being pictured.

Wrapped in the Flag

Images of soldiers with weapons and the suffering of their victims portray

individuals in standard wartime roles. Another set of images frames war and

protest in terms of a more communal symbol; the

flag. Flags are critical symbolic components of

both the larger war-peace process and also of its news media

dimension. The American national anthem i s entitled "The Star Spangled

Banner," and it reminds us that "the flag was still there." A recent Clint

Eastwood film, "Flags of Our Fathers," centers on the iconic photo of six U.S.

Marines raising the U.S. flag on Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima. Public

support for war, we believe, includes a "rally round the flag" effect.

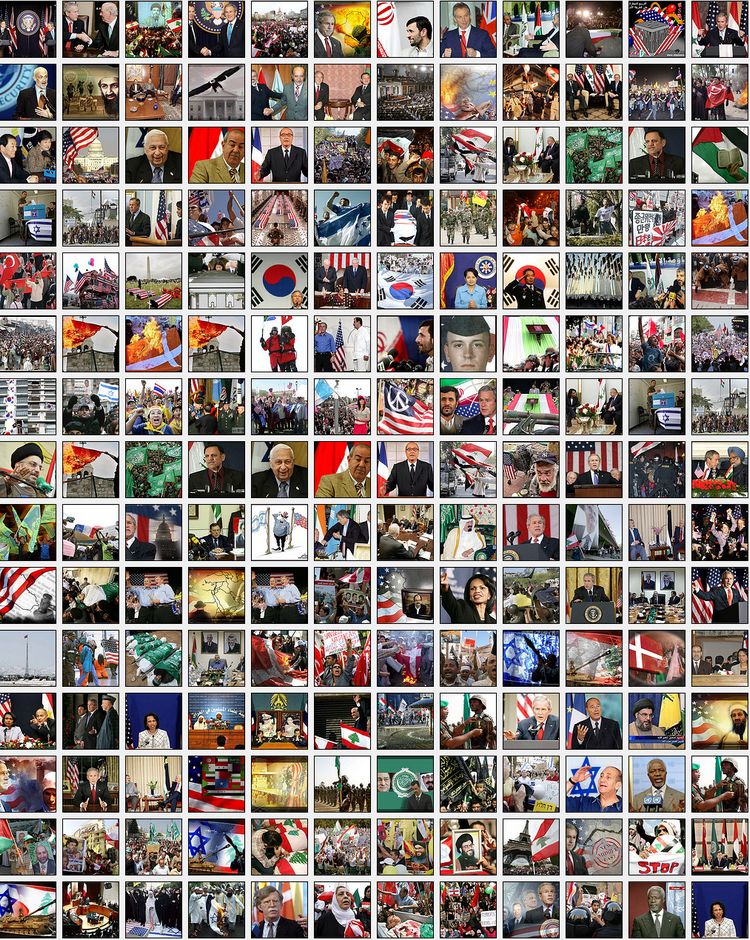

Of the approximately 2000 photo images we collected from the Aljazeera

[Arabic] webiste during 2005-2006, there are something over 350 photos that

include a flag. This following composite image includes tiny views of

many of them.

These are some of the photo images we use to investigate the importance of

flags in the news media and how flags frame war and peace.

War is not limited to soldiers with weapons; death, destruction, and

suffering. It includes other worlds of meaning that try to put war

actions and events in a larger frame. Flags provide some purpose,

some way of life that can provide a larger meaning. So this is

also the war zone.

Flags and States

The uses of the flag that we point out below all depend on the identification

of flag and state. The flag becomes the visible symbol of "we" -- our people

and our state. We assume the identification is present in all of the photo

images though in some images the flag plays a rather mundane role. Even though

we believe that it is always present, only in some cases does the

identification becomes so strong that it cannot be missed.

Whether wrapped around the neck of chess pieces or joined in multi-faceted

interaction there can be little doubt that Aljazeera [Arabic] used the flags

to represent two states--the United States and Iran. But it is only plausible

for them to make these constructions if they can be confident the readers will

recognize their identification of flags and states. Otherwise they would be

interesting but mysterious photo images.

Political

cartoonists also identify states with flags. They have something they

want to 'say,' but the saying is limited to pictures. In this cartoon it seems

clear that the cartoonist has in mind the relationship between Israel and the

US rather than being simply a drawing with two flags. Unless the cartoonist

can assume that the audience looking at the image will make that

identification the cartoon loses its point.

Political

cartoonists also identify states with flags. They have something they

want to 'say,' but the saying is limited to pictures. In this cartoon it seems

clear that the cartoonist has in mind the relationship between Israel and the

US rather than being simply a drawing with two flags. Unless the cartoonist

can assume that the audience looking at the image will make that

identification the cartoon loses its point.

Aljazeera [Arabic] quite self-consciously identifies flag and state, and they

can do this because they assume their audience does the same.

Flags and Leaders

Flags

are ubiquitous -- they can be found in all corners of the world. We have

pictures of flags from North America, South America, Western Europe, the

Middle East, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific nations in the 350 plus photo

images.

Flags

are ubiquitous -- they can be found in all corners of the world. We have

pictures of flags from North America, South America, Western Europe, the

Middle East, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific nations in the 350 plus photo

images.

Some actors even have two flags to reflect the people of whom they are a part.

Sheikh Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah of Hezbollah, for example, stands

beside both the Hezbollah flag and the flag of Lebanon. In the

multi-community state of Lebanon more than a single flag visualizes the

cleavages that divide them and the community that binds them together -- even

if the binding of community is somewhat tenuous.

Leaders may be given something of the iconic character given to flags.

Nasrallah is Hezbollah; to see him is to see Hezbollah. Of course, he is not

Hezbollah. But in the communication, as his picture becomes part of the story

over and over, he becomes the iconic symbol of Hezbollah.

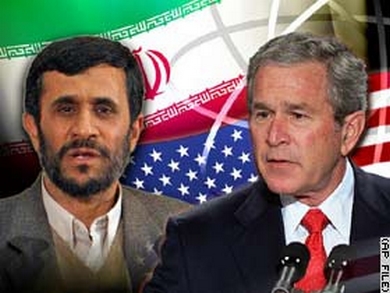

We see the same iconic character in the two photo constructions of Iranian and

U.S. presidents Ahmadinejad and Bush below.

Flags and leaders are joined in the left photo construction; the presidents,

the flags become the visible figure of the states. And on the right it is

al-Qaeda versus the United States: the flag as US; bin Laden as al-Qaeda.

Politicians Wrap Themselves in the

Flag

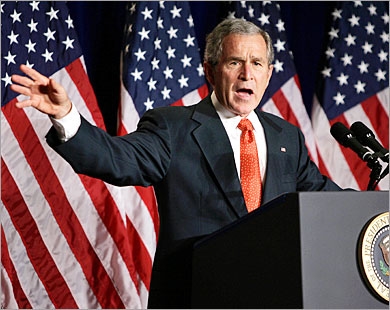

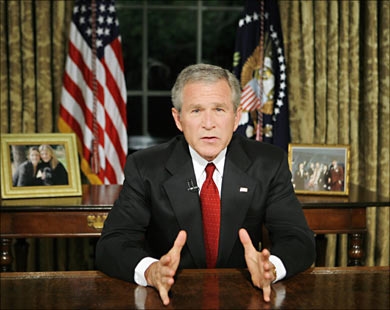

When Mr. Bush speaks it is the state speaking. He does not stand alone.

Instead surrounded by the symbol of state -- not just one, but many flags --

he becomes the authoritative voice of the United States. He draws on the flags

to authenticate his speaking.

So we say, politicians wrap themselves in the flag. By surrounding themselves

with flags they legitimate the identification of their actions with the state.

Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki may have been more in need of the

legitimacy that wrapping himself in the flag might yield than President Bush.

He and his government were in serious trouble as sectarian conflict took the

country toward full scale civil war. Mr. Bush was not far behind, however. The

picture appeared on the Aljazeera [Arabic] website October 21, 2006. He was

about to lead his political party to defeat. In only a few weeks he would

become a president whose speaking for the state had been rejected in the

voting booth, and all the flags he could assemble would not save him and his

party. The political problems of the two leaders did not stop them from trying

to leach legitimacy from the flags, however.

More than 150 of the 350+ pictures involve political leaders and

flags. It is the largest subset of the pictures by far. The leaders stand

in front of flags, as above. They stand beside flags. They sit close

to flags. They sit around a table with the flag over in the corner. They get close to flags in great variety of poses.

In the 'I don't care what you say about me as long as you spell my name right"

contest Mr. Bush is the clear winner. His picture appears on the Aljazeera

[Arabic] website 32 times either alone or with other foreign leaders.

Number Appearances

|

Political Leader

|

32

|

Bush, U.S.

|

19

|

Rice, U.S.

|

11

|

Haniyeh, Palestine

|

8

|

Abbas, Palestine; Blair, UK

|

6

|

al-Maliki, Iraq

|

5

|

Ahmadinejad, Iran; Chirac, France; Nasrallah, Lebanon; Rumsfeld, U.S.

|

What is clear from the table is that the important news of 2005-2006 for

Aljazeera [Arabic] was conflict in the Middle East: Iraqi civil war;

Israel-Palestine conflict; world concern about Iranian nuclear development;

and conflict between Israel and Lebanon as well as within Lebanon. The persons

listed in the table are there because of their participation in these

controversies. That Aljazeera [Arabic] focussed on these controversies is not

a surprise, but these were also important foci for BBC World and CNN World.

Conflict provides the opportunity for leaders of states

and movements to wrap themselves in the flag in front of a camera

and try to mobilize support for wars and protests.

Attacks and Protests

How do you attack a state without taking up arms?

Just as the flag is a useful symbol for politicians who attempt to draw

legitimacy from it, the flag is a useful symbol for those who would attack the

state. These are Hezbollah women who, in the fall of 2006, show their contempt

for the attacking state, Israel, and its sponsor, the United States. They

carry the flag of Hezbollah high. The flags of Israel and the US are fit only

to be trampled. They are stomped across by hundreds protesting the deaths

Israel inflicts and the US approves.

The most sustained example of using the flag as protest in 2006 grew out of

the controversy concerning the publication of cartoons of Muhammad in a Danish

newspaper.

You have desecrated our sacred symbol and we will desecrate yours. And across

the muslim world the flag of Denmark was burned. The protests and flag

burnings spread from Denmark to the Middle East and then to Africa and

Indonesia. They treated the flag as a parallel sacred symbol with the prophet.

The sacred symbol of western civilization was identified as the flag, which

serves as symbol of nation-state, in their protests. [See Beer and Boynton,

2006

http://myweb.uiowa.edu/gboynton/cartoonprotests/cartoonprotest.html]

Flags were used to identify the villain.

In the photo on the left the 'evil' is in the foreground: prisoners being

tortured and abused. The perpetrator is identified by the flag. In the photo

on the right the stars are gone and the peace symbol replaces it. The

transposed flag becomes protest against war and an appeal for peace, while

identifying the perpetrator of the war as the US.

In the protest, the flags may be used to identify the "us" and to bind "us"

together.

We are Hamas. We will not bend. We have been killed, mutilated, and

humiliated by superior force. We respond in protest bound together

by our suffering and our flag that is the visible symbol of

who we are.

Giving Suffering Broader Meaning

The flag is used, finally, to give war's suffering a broader

meaning. In the formal world of the US military, the coffin is

symbolically wrapped in the flag, as the flag drapes the soldier's tomb.

The coffin of steel. The formal uniforms. The tightly folded flag. And the face

in the background. In death is the state.

And in the less formal world of the Middle East this is how the sacrifice is

given broader meaning.

Again the flag. The flag of Lebanon draped over coffins. The small child

wrapped in the flag of Hezbollah. When you die for the state you do not die in

vain.

Memes and Meanings

The images of war and protest that we have shown

above present war and protest in alternative symbolic frames. These

frames help media elites and their audiences to interpret war in the

contexts of multiple worlds of meaning.

The images are not simply

random visual detritus thrown up by the events. They are examples of

repetitive themes, critical tropes. They are, in the vocabulary of

evolutionary theory, memes -- elements in self-replicating cultural systems of

war and protest (Beer, 1999

http://jom-emit.cfpm.org/1999/vol3/beer_fa.html;

International Studies Quarterly, 1996).

The memes of soldiers and

weapons; death, destruction, and suffering are important repetitive markers of

individual experience. At the same time,flags are central visual symbols of

larger political communities. Political leaders use flags, together with other

such symbols, to mobilize and motivate their followers for war and

protest. The globalizing media carry the news.

References

Beer,

Francis A. 1999. "Memetic Meanings," Journal of Memetics 3,

1

(1999). http://jom-emit.cfpm.org/1999/vol3/beer_fa.html

Beer,

Francis A. and G. R. Boynton. 2007. North-SouthGlobalization and Action

Initiatives: Multiple News Media in the Emerging Global Communication Space,”

(with G. R. Boynton) in Rafael Reuveny and William R. Thompson, North and

South in the World Political Economy

(London

UK:

Blackwell).

Beer,

Francis A. and G. R. Boynton. 2006.“Globalizing Resistance: Global

Media and the Political Psychology of Oppression and Resistance.” Paper

presented at the International Society for Political Psychology,

Barcelona,

Spain,

July

12-18.

http://myweb.uiowa.edu/gboynton/cartoonprotests/cartoonprotest.html

Beer, Francis A. and G. R. Boynton. 2004. "Globalizing Political Action:

Building bin Laden and Getting Ready for 9/11",

The American Communication

Journal 7 (2004).

http://www.acjournal.org/holdings/vol7/index.htm

Beer, Francis A. and G. R. Boynton. 2003. "Globalizing Terror",

POROI Journal 2, 1

http://inpress.lib.uiowa.edu/poroi/papers/beer030725_outline.html

Boynton, G. R.

2006. "Size Matters."

http://globalizing.wordpress.com/2006/12/07/size-matters

Entman, R. 2003. Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion and U.

S. Foreign Policy. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hariman Robert and Lucaites and John Louis Lucaites,

2007.No

CaptionNeeded: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy.

Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.

International

Studies Quarterly: "Special Issue, Evolutionary Paradigms in the Social

Sciences," 40, 3 (September, 1996).

Lakoff, George. 2006. "Simple Framing."

http://www.rockridgeinstitute.org/projects/strategic/simple_framing

Nelson, John S. and G. R. Boynton. 1997. Video Rhetorics: Televised

Advertising in American Poloitics. Urbana IL: University of Illinois

Press.

Norris, Pippa. 2003. Framing Terrorism. London UK: Routledge.

Political

cartoonists also identify states with flags. They have something they

want to 'say,' but the saying is limited to pictures. In this cartoon it seems

clear that the cartoonist has in mind the relationship between Israel and the

US rather than being simply a drawing with two flags. Unless the cartoonist

can assume that the audience looking at the image will make that

identification the cartoon loses its point.

Political

cartoonists also identify states with flags. They have something they

want to 'say,' but the saying is limited to pictures. In this cartoon it seems

clear that the cartoonist has in mind the relationship between Israel and the

US rather than being simply a drawing with two flags. Unless the cartoonist

can assume that the audience looking at the image will make that

identification the cartoon loses its point. Flags

are ubiquitous -- they can be found in all corners of the world. We have

pictures of flags from North America, South America, Western Europe, the

Middle East, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific nations in the 350 plus photo

images.

Flags

are ubiquitous -- they can be found in all corners of the world. We have

pictures of flags from North America, South America, Western Europe, the

Middle East, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific nations in the 350 plus photo

images.